CAPTURING THE STRUGGLE FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE IN PHOTOS

by Nick Rahaim

Tropics of Meta: historiography for the masses - November 11, 2020

https://tropicsofmeta.com/2020/11/11/the-david-bacon-photography-archive-capturing-the-struggle-for-social-justice-in-photos/

Stanford Libraries, Special Collections

https://library.stanford.edu/blogs/special-collections-unbound/2020/11/david-bacon-photography-archive-capturing-struggle-social?fbclid=IwAR3Wji2Df54rbubxa6xwyO2qw7wZz9wFDGXa7No5bjmBXvDhgN1BEU5di7o

The hands of Manuel Ortiz show a life of work

Manuel Ortiz held out his hands to the camera, revealing decades of toil - callouses, scars and creases embedded with soil that multiple hand washings wouldn't scrub clean. Photographer David Bacon first saw him in 2015 as he pushed a shopping cart full of cans and bottles through an alley in Yakima, Washington. Ortiz first came to the United States in the 1950s under the Bracero program and continued working the agricultural fields of California and Washington for six decades.

But when he met Bacon, Ortiz was in his mid-80s and too old to work in fields, so he redeemed cans and bottles to cobble together enough money for rent and food. With a single photo in Bacon's signature style - an uncropped black and white image set in a hard black border marking the edge of the full frame - he captured decades of hard labor that provided food for millions, but more importantly he reveals the continued strength Ortiz's hands hold to survive in a society that had continually undervalued his work.

"It's a powerful image," said Roberto Trujillo, associate university librarian and director of Stanford Libraries' Special Collections. "An elderly man's hands, just his powerful hand, scarred and worn from working in the fields day in and day out for probably all his adult life."

The photograph of Ortiz, entitled "The hands of Manuel Ortiz show a life of work," is one of 200,000 images spanning three decades shot by Bacon that are now housed in Stanford Libraries' Special Collections, which acquired Bacon's archive in the winter of 2019. The collection was launched this fall under the exhibit title Work and Social Justice: The David Bacon Photography Archive at Stanford, after more than a year of cataloging the images, original film negatives, color transparencies and digital files.

"David Bacon's career as a photojournalist and author represents working class history and social justice movements that transformed political landscapes internationally," said Ignacio Ornelas Rodriguez, Ph.D., a historian who works in the Department of Special Collections at Stanford who worked closely with Bacon on the acquisition of his archive. "David's work highlights communities that are often ignored by mainstream media and brings them from the margins of society to the forefront."

Bacon, 72 and a labor organizer-turned-photojournalist, has been at the frontlines of social justice movements since his youth, starting as a student activist in the Free Speech Movement in Berkeley in the mid-1960s. In the mid-1980s, after working as an organizer for the United Farm Workers and the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union, among others, Bacon picked up a camera and began training his lens on the people he had worked with closely for nearly two decades. In the subsequent years, Bacon documented workers in the fields, strikes by teachers and hotel workers in cities, poverty and homelessness in the streets, May Day marches for immigrants' rights and even the struggle of Iraqi workers during the United States' occupation of the country following the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in 2003.

"Activism, the feeling this work is part of a movement for social justice has been central to everything I've done," Bacon said.

His work has brought him to Asia, Europe and throughout Latin America and has revealed the human faces behind many political struggles. But there's a common thread tying every photo together: People banning together to fight corporate greed, globalization and politics that both divide and displace workers and their families.

"What has always impressed me with David's work is how he purposely tried to capture the humanity of people who are struggling to make it, to just survive," Trujillo said. "His work also deals with labor and laborers at an international scale that's quite impressive for the work of a single man."

The David Bacon Photography Archive complements the Bob Fitch Photography Archive, which boasts 200,000 images from the civil rights movement and farm worker struggles of the 1960s and 1970s. Together the two archives provide nearly 400,000 images covering six decades of social movements in California and beyond.

The hands of Manuel Ortiz show a life of work captured in the single image, through the David Bacon Photography Archive at Stanford, a life's work in photos will be maintained in perpetuity. Scholars and writers scouring the archives of labor and immigrant rights activists including Bert Corona or of organizations like California Rural Legal Assistance and National Council of La Raza, all held at Stanford Libraries' Special Collections, now have access to the faces and human form behind the primary-source documents on the struggle for social justice.

Bert Corona, father of the modern immigrant rights movement, and his son, Ernesto

Bert Corona looks intently into Bacon's camera lens, but there's something enigmatic in his expression - a bemused seriousness or perhaps a stern contentment. Over Corona's left shoulder stands his young grandson, Eduardo, who's approaching adolescence and gives a quizzical look as the tip of a small American flag rises toward his face. The following year, 2001, Corona will pass at 82 years old.

"That image of Bert just stuck out," Trujillo said. "It's Bert, it's just Bert. It shows his anger, his humanity, his compassion and his passion for his work."

Corona's name might not have the recognition of some of his contemporaries in the labor and Chicano rights movements of the middle 20th century, but his impact still shapes the political landscape in California today.

"He was the father of the modern immigrant rights movement because it was Bert who said that the Mexican people, especially Mexican workers, living in the United States, especially in LA, were going to be the basis for radical social change, and he was right," Bacon said. "A lot of the work I have in archive chronicles and documents the latter part of that history."

In the 1930s Corona became an influential member of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) where he organized low-paid, mostly Spanish speaking workers in Los Angeles. Outside of labor organizing, he was active in many early Mexican American political groups including El Congreso de Pueblos de Habla Española and the Asociación Nacional Mexicano Americano. By the rise of Chicano movement in the 1960s, Corona was already a respected elder statesman who was one of the earliest champions of the rights of undocumented workers when much of the labor movement was hostile to them. For Bacon, there's a direct through-line from Corona's early activism to the May Day marches that bring millions to the streets demanding justice and dignity for those without papers.

This concern for the undocumented likely grew from Corona's binational childhood on the border. His father was an anarcho-syndicalist who was a comandante in Francisco Villa's Division del Norte during the Mexican Revolution, but had to flee after post-revolution politics in Mexico made it dangerous for him to stay in Mexico. He moved to El Paso, Texas where Corona was born. This also marks a similarity with Bacon's own life: Bacon's father was a printer and union leader in New York City who ended up on a McCarthy-era blacklist for alleged communist ties and lost his job in 1953. So at a young age Bacon moved with his family from Brooklyn to Oakland, California where his father was able to find work.

Corona's father would later be granted amnesty by the Mexican government only to be murdered shortly after for his political activity. The Bacon family was never exposed to violence, but the experience of being uprooted at an early age because of political persecution informed Bacon's politics and shaped his approach to photography.

On the Mexican side of the border wall between Mexico and the U.S. families greet other family members on the U.S. side.

In the global economy capital faces few barriers while crossing international borders, while people face many. Few images capture this fact as starkly as three family members standing at a rusted border wall with chipped paint worn by weather and sun. An older woman has placed her hands on the wall, intently looking at a family member on the other side who is hidden from view. Her face is full of love, but there is little joy in her expression, rather a longing for an embrace she's legally prohibited from giving.

Bacon took this photo at Parque de Amistad, or Friendship Park, in Tijuana, Mexico in 2017. Every Sunday families gather at the park, close to where the border wall runs into the Pacific Ocean, to speak with loved ones through metal grates. The family pictured came 1,500 miles from the state of Puebla in central Mexico for the chance to see their family.

Much of Bacon's work has focused on the border and migration, as neither are separated from the struggle for justice in fields, factories and hotels. In fact he has written numerous books on this nexus, including: The Children of NAFTA (2004), Communities Without Borders (2006), Illegal People - How Globalization Creates Migration and Criminalizes Immigrants (2008), The Right to Stay Home (2013) and In the Fields of the North/En Los Campos del Norte (2017).

While borders, walls and inhumane immigration policies keep people separated, the solidarity in the struggle Bacon has spent a lifetime documenting knows no borders.

Jane Algoso cuts dead fronds from the trunks of banana trees

Jane Algoso should have been in school, but the 11-year-old held a sickle to cut dead palm fronds from the trunk of a banana tree in Mindanao, Philippines for 50 peso a day. The child wore rubber boats to navigate the muddy ground in the Soyapa Farms banana plantation. Algoso looks strong and healthy, but she's in the middle of a chemically intensive monoculture controlled by the Dole Food Company.

Bacon travelled to the Philippines in 1997 to report on child labor and strikes by four cooperatives against the poverty-level prices Dole paid for their harvest. In a struggle to survive, many farmers pulled their children out of school to help in the fields. Bacon's article and photos ran on the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle on Christmas Day that year. His writing and pictures of Algoso and other children working in plantations added to the growing international pressure on Dole to meet the demands of the striking farmers and pay fair prices. With better pay farmers would be able to send their children to school.

"After they won their strike prices went up," Bacon said. "I went back to the community 20 years later to meet with the same people and I saw they were living a good life compared to what things were like before."

While Bacon went to the Philippians to document Filipinos organizing against exploitation by a large corporation from the United States, many photos in the David Bacon Photography Archive also document Filipinos organizing in the United States. From the earliest days of the United Farm Workers movement, Filipino Americans organized alongside Mexican Americans for justice in the fields.

Under globalization that started to accelerate in the 1990s, unions, strikes and protections against child labor were seen as "barriers to trade." Activists from across the globe descended on Seattle, Washington in November of 1999 to protest the World Trade Organization (WTO) Ministerial Conference and free trade agreements that would hurt working people in the pursuit of greater profit and economic growth. The example of children working in banana trees was one among myriad grievances brought by activists.

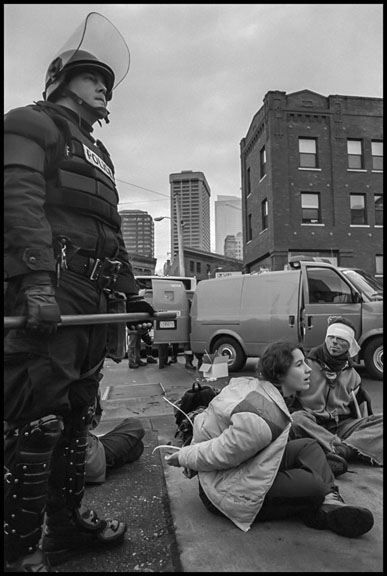

Police arrested demonstrators as they sat in and blocked intersections

A police officer in full body armor stood motionless holding a baton with eyes resting intently on something out-of-frame. At his feet were protesters sitting on the pavement with their hands zip tied behind their backs. A young woman's mouth hung slightly ajar with a look of exasperation on her face. To her left, a man with a bandaged head and scrapes on his face looked at the police officer with displeasure.

Bacon went to what would later be known as the Battle of Seattle and reported on the protests against unchecked global capitalism. More than 40,000 people took to the streets, in a coalition of labor unions, indigenous groups, environmentalists and international NGOs. There were marches, rallies, teach-ins, and a few acts of vandalism.

Some sat and laid in intersections to block traffic in direct actions to disrupt the WTO talks, many of whom were arrested by police. As demonstrations intensified police met protesters with rubber bullets and teargas. The global talks failed amidst the maylay and hundreds of people were arrested by police - 157 of whom were found to have been detained without probable cause and received settlements from the city of Seattle.

Thirty-five years prior in Berkeley, California, Bacon left a demonstration in handcuffs. Early in the Free Speech Movement he took part in the occupation of Sproul Hall at UC Berkeley in December 1964 and was the youngest person arrested. Bacon was still attending Berkeley High School but was enrolled in classes at the university at the time.

"Our finals were given while I was in jail and the university didn't let us take an incomplete or retake the final," he said. "For all intents and purposes I was thrown out, many others were too."

So Bacon, bypassed his formal academic studies and went to the factory floor before becoming a full-time union organizer like his father before him.

Outside the labor camp, the children of strikers at Sakuma Brothers Farms set up their own picket line on a fence at the gate

Six children stood on a bench behind a barbed-wire fence giving toothy, excited smiles to Bacon's camera in 2013. They had set up their own picket line as their parents went on strike for union recognition and better pay in Burlington, Washington, about an hour north of Seattle. One boy raises a fist in solidarity and a girl holds a placard that reads Justicia Para Todos, justice for everyone.

Most of their parents had migrated from to the United States from indigenous communities in Mexico for work and for a better life for their families. But work in the fields picking blueberries at Sakuma Brothers Farms left them both physically exhausted and in poverty, raising their children in labor camps. They formed a union, Familias Unidas por la Justicia, and organized for official recognition, better wages and living conditions.

Bacon's photo of the children not only showed who would benefit most from a just labor deal, but became the image Familias Unidas por la Justicia used to promote their efforts. The young girl holding the placard was incorporated in the union's logo and was printed on t-shirts.

"As a photographer I'm also a participant," Bacon said. "I want people looking at the pictures to feel what it is to do the work of farm workers and others, but I also want the images to be useful to the people who are in them."

Three years later in 2016, workers at Sakuma Brothers Farms, the largest berry grower in Washington state, formally voted to form the union, even though their union rights as farmworkers were not recognized by the National Labor Relations Board. In an article about the organization effort for the Nation, one union member told Bacon, "From now on we know what the future of our children is going to be."

An archive of one's life work is inherently backward looking. A collection of photographs documenting social struggle often lacks the lightness of being. But, the humanity and dignity shown in the David Bacon Photography Archive gives hope. The markers of the slow progression of social justice many images capture give direction to the path forward, guiding toothy-grinned kids as they mature into adults.

Nick Rahaim is multimedia journalist and storyteller based in Monterey, California. He was a member a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporting team at The Press Democrat who covered the North San Francisco Bay wildfires in 2017. Rahaim's articles have appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle, Vox and Hakai Magazine among many other publications. In addition to journalism, he has worked in commercial fisheries from the Bering Sea to Southern California for the better part of a decade. Check out his blog at outside-in.org and follow him on Instagram and Twitter @nrahaim.

No comments:

Post a Comment