WILL THE SUPREME COURT OVERRULE FARMWORKER UNION RIGHTS?

By David Bacon

Capital & Main, November 20, 2020

https://capitalandmain.com/will-the-supreme-court-overrule-farmworker-union-rights-1120

An organizer talks at lunchtime with a D'Arrigo Brothers worker with a union button on her cap.

All photos by David Bacon. These photos are housed in the Special Collections of the Green Library at Stanford University. https://exhibits.stanford.edu/bacon

Sidebar below: How a Labor Law Evened the Balance of Power in California's Fields

Not long before Donald Trump's election in 2016, the Pacific Legal Foundation filed suit against California's farmworker access rule in federal court on behalf of two companies - Cedar Point Nursery in Siskiyou County and the Fowler Packing Company in Fresno. The foundation is a conservative libertarian group that holds property rights sacred and campaigns against racial equity. It fought hard for the appointment of Amy Coney Barrett to the high court.

The access regulation, which took effect after the passage of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act in 1975, allows union organizers to come onto a grower's property in the morning before work to talk with workers. According to the labor board's handbook, "The access regulations of the Agricultural Labor Relations Board are meant to insure that farm workers, who often may be contacted only at their work place, have an opportunity to be informed with minimal interruption of working activities."

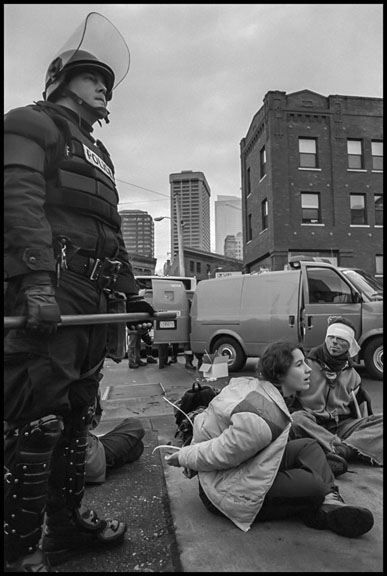

Two UFW organizers walk into a D'Arrigo Brothers broccoli field in Salinas, 1994.

The board requires that the union give notice to the employer before taking access, and that organizers not disrupt work. They can talk only for an hour before and after work and during lunch, and can take access for only a total of 120 days during a year.

Growers have always hated the access rule, and many at first refused to obey. Former United Farm Workers organizer Fred Ross Jr. remembers being arrested several times in Santa Maria for taking access. "This was all about power and who had it," he says. "Growers had it all, and their workers none. They wanted to dominate. For them, workers didn't even have the right to talk."

The suit filed by the PLF, Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid, attracted more than the predictable support of the California and American Farm Bureaus. Amicus briefs came from a host of right-wing legal bodies, including the Mountain States and Southeastern Legal Foundations, the Pelican and Cato institutes, and even the Republican attorneys general of Oklahoma, Arizona, Arkansas, Kentucky, Missouri, Nebraska and Texas. The company brief conjured up visions of "stampedes of third-party organizers" and warned, "If such a rule proliferates, property owners throughout much of the nation will see their rights greatly diminished as governments increasingly sanction invasions of their property."

Had the political atmosphere in the country not changed in the 40 years since the regulation has been in effect, the suit might never have been filed at all. Agribusiness challenged the access rule from its inception and went all the way to the California Supreme Court, where the growers lost in 1976. In the last decade, however, visions of a liberal U.S. Supreme Court evaporated in the final years of the Obama administration, and Trump's election led to the appointment of three right-wing justices, giving the court a 6-3 conservative majority.

When the U.S. Supreme Court agreed on Nov. 13 to hear the growers' appeal from their loss at the U.S. Court of Appeals, many legal observers became concerned. "State court decisions over state issues used to be respected by the U.S. Supreme Court," says Jerry Cohen, who helped write the law as the legal director for the UFW. "States' rights used to be a Republican issue. Now the end product is all that matters."

That end product is a continued erosion of power for farmworker unions. "Without the rule the union seems to workers like it's not legitimate, and there really is no right to talk," Ross says. "Losing it reinforces the growers' power and control. It's one more blow to the right to organize."

The mundane genesis of the current suit was a short strike in Dorris, near the Oregon border, where hundreds of farmworkers migrate from Southern California every year to trim young strawberry plants. In 2015, according to one worker, Jessica Rodriguez, the company paid low wages, had dirty bathrooms and harassed and intimidated workers. They called the United Farm Workers, which sent organizers and filed under the access rule to talk with them on the property. The strike lasted for just a day. At Fowler Packing the union filed for access to talk with an unrelated group of workers, and the company simply refused to let organizers onto the property.

Over the years the access rule became a valuable tool for organizing workers. Jerry Cohen remembers his discussions with UFW founder Cesar Chavez, during negotiations with then-Gov. Jerry Brown, who signed the law during his first term in 1975. "Cesar told us to get things that were practical, that could help workers organize," he recalls. "Where workers are together it's easier for the union to talk with them."

The access regulation came into effect at a time when the UFW was strong. The balance of power between workers and growers had shifted, and by the early 1980s more than 40,000 farmworkers had union contracts. To Eliseo Medina, who grew up in a farmworker family and became a leading organizer, "The rule was a very clear example that growers were not all-powerful. It was a huge change. People saw organizers coming onto the properties, and could have a conversation at work about their future. It gave people confidence that change was possible."

In 1996, when a huge campaign began to organize the strawberry industry in Watsonville, organizers visited picking crews in dozens of fields. They taped butcher paper on the walls of the Porta Potties, and held meetings where strawberry workers wrote down their demands for raising some of the lowest wages in agriculture, for health benefits and an end to discrimination in hiring. Then in field meetings they planned marches to the company offices, where the demands were announced.

In 2015 the access rule was used in McFarland in the San Joaquin Valley, where workers angry over a wage cut went on strike. They called in UFW organizers, who used meetings in the fields during lunch and after work to collect signatures on an election petition. After workers voted overwhelmingly for the union, the blueberry pickers chose a ranch committee and eventually negotiated a contract with Gourmet Trading.

When Pacific Legal Foundation argued its case in 2017 before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, where it ultimately lost, its attorney Wen Fa declared, "The growers have no problem in the union talking with workers. It's where they talk with the workers. ... [There are] plenty of alternative means for the union to talk with workers ... All the workers [at Cedar Point Nursery and Fowler Packing Company] live in houses or hotels. Many have cellphones."

The ALRA had recognized, however, that it's harder for farmworkers to organize than for other workers, and set up a much quicker process for gaining union recognition than the National Labor Relations Act did for other workers in 1936. Because farmworkers work only for a season, which can last just weeks, union representation elections take place a week after workers petition for them, and within just 48 hours if there's a strike.

Growers are required to furnish a list of workers with addresses. "Those lists are notoriously bad, though," Medina laughs. Most Cedar Point workers actually live hundreds of miles from their seasonal jobs. Addresses in Mexico are very hard to find, and workers on this side of the border often live in isolated colonias scattered over a huge geographical area. "By winning access it was easier to get their addresses so we could visit them, especially those who were afraid to talk in front of the foreman," Ross explains.

The difficulty of reaching workers outside of work is even greater for a growing segment of the farm labor workforce- those workers brought to the U.S. under temporary H-2A visas. In 2019 the U.S. Department of Labor allowed California growers to fill 23,321 jobs with these contract laborers. "H-2A workers would be even more impacted by losing the access rule," Medina charges. "They don't have the legal right to organize - even undocumented workers have more rights than H-2A workers. They're living in barracks under the growers' 24-hour control. In Delano growers are taking over whole motels and making them into labor camps."

The union, however, has used the access rule less frequently over the years. In her defense of it, ALRB chairwoman Victoria Hassid noted that it filed for access at only 62 of the 16,000 agricultural employers in California in 2015. "There is no indication," she wrote, "that the access regulation poses a significant problem for California farms ... petitioners have not actually alleged any negative economic impact on them (or anyone else) resulting from the regulation."

Pacific Legal Foundation's Wen Fa made the growers' root argument in response: "The Constitution forbids government from forcing property owners to allow unwanted strangers onto their property, and there is no exception for union activists."

In an interview with this author, Fa claimed that growers' economic losses growing out of the access rule could be "significant," but couldn't say specifically what they are. "This case is about property rights," he said. In his winning defense of the access rule before the U.S. Court of Appeals, Matthew Weiss, deputy attorney general for the ALRB, noted that the effort to knock out the rule simply "privileges private property interests over all others."

UFW general counsel Mario Martinez says the effort to knock out the access rule is further evidence of a history of racism toward farmworkers.

"The federal government has excluded farmworkers from all labor law protections under the National Labor Relations Act for 85 years," he charges. "In light of this racially discriminatory exclusion, California granted to agricultural workers important labor protections to balance the historical imbalance of power between farmworkers and growers. A court review of California's legislation appears to be another attempt to unfairly discriminate."

The U.S. Supreme Court plans to hear arguments in the case early next year and will probably rule by July.

HOW A LABOR LAW EVENED THE BALANCE OF POWER IN CALIFORNIA'S FIELDS

By David Bacon

Capital & Main, November 20, 2020

https://capitalandmain.com/how-a-labor-law-evened-the-balance-of-power-in-californias-fields-1120

In the winter of 1976, a year after the Agricultural Labor Relations Act took effect, lettuce cutters at George Arakelian Farms Inc. began organizing a union. The men lived in Mexicali, Mexico, just south of California's Imperial Valley. Every day they left home at 2 a.m. and walked to the border. After crossing it, the company labor contractor put them into cars. As each clunker was filled, it took off for the Palo Verde Valley, a two-hour drive across the desert.

Union organizers also met the workers at the border and followed the cars. When they all arrived at the fields, however, the crews couldn't immediately start work. In the winter, water freezes inside the lettuce. If a cutter grabs a head to harvest it, the ice cuts into the leaves and they wilt. Everyone has to wait for the ice to melt, when work can start.

Next to the fields, workers lit fires in 55-gallon drums. In those moments when they stood warming their hands and talking with the organizers, the union at Arakelian Farms began to take form. The laborers asked about the benefit plans, their rights under the new labor law and when they might be able to vote the union in. They set up a ranch committee to make decisions and convince the unconvinced.

When the ice finally melted, they began to cut, almost running down the rows with their knives. Packers followed, tossing boxes of lettuce onto trucks. No one took lunch. When the company filled its daily order, workers jumped into their cars and drove back to the border. They walked home with just with enough time to eat, say hi to their kids, catch a few hours' sleep, and then wake up again and leave at 2.

Organizing their union this way was possible because of the access regulation, formulated by the Agricultural Labor Relations Board. The regulation allowed the organizers to come onto Arakelian's property in the morning before work to talk with the lettuce cutters. After a few weeks of field meetings, workers and organizers filed a petition for an election, which the union won 139-12.

Like many growers, however, Arakelian refused to negotiate a contract. It took nearly 10 years before the California Supreme Court found Arakelian had violated its obligation to bargain with its workers. Other parts of the law had to be changed to solve that problem, and George Arakelian Farms is no longer in business. The workers have moved on. But from the beginning, the access rule was the tool they, and others like them, used to help even the balance of power with the growers.