FIGHTING FOR BREATH BY A DYING SEA

By David Bacon

Sierra Magazine, January/February 2018

https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/2018-1-january-february/feature/salton-sea-dying-we-cant-let-happen

At the edge of the Salton Sea, in Salton City, the salts dissolved in the sea's water leave a dry crust on the soil as the sea dries up and the edge recedes. On the hardpan are dead fish, left behind as the water recedes.

When the dust rises in North Shore, a small farmworker town at the edge of the Salton Sea, Jacqueline Pozar's nose often starts bleeding. Her teacher at Saul Martinez Elementary School in nearby Mecca calls her mom, Maria, and asks her to come take her home.

Jacqueline is seven years old. "I feel really bad because I can't do anything for her," Maria Pozar says. "Even the doctor says he can't do anything - that she's suffering from the dust in the air. Most of the children in North Shore have this problem. He just says not to let them play outside."

The children of North Shore are the proverbial canaries in the coal mine, whose sudden illnesses warn of a greater, life-threatening disaster to come. That disaster is the rapidly receding waters of the Salton Sea. As more and more playa - the sea's mud shoreline - emerges from the water and dries out, fine particles get swept up by the wind and coat everything in its path, including children's noses.

Airborne particles ranging in size between 10 and 1 µm, called PM 10, are generated from wind-blown dust. When they lodge in the lungs, they can cause asthma and other illnesses.

Maria and Yesenia Pozar are farmworkers, and indigenous Purepecha immigrants from Mexico. Except for baby Leslie, all the children suffer nose bleeds when the dust blows into their homes in North Shore, in the Coachella Valley, from the dry border of the Salton Sea.

"This will be the biggest environmental disaster of our time," charges Luis Olmedo, director of the Comite Civico del Valle, a community organization in the Imperial Valley at the Sea's south end. "The issue of the Salton Sea trumps everything. We have to get the air contaminant level to zero. There is no safe level for the contaminants we have here. We need an intermediate project to stabilize the shoreline. The sea is receding much faster than any projects moving forward."

The Salton seabed was created by the Colorado River millions of years ago. As it dug out the Grand Canyon, river sediment filled in a delta at the north end of the Gulf of California, creating what are now the Coachella and Imperial Valleys. Between those valleys lay an ancient geologic depression reaching a depth of 278 feet below sea level. Over the millennia it filled with water and then dried out repeatedly, but by the time of the Spanish colonization it was a dry desert saltpan.

In 1905, as Imperial Valley growers were building canals to bring Colorado River water to irrigate their farms, the levees containing their diversion failed when the river flooded. For two years the Colorado poured into the depression, creating the Salton Sea, whose surface rose over 80 feet above the desert floor.

Evaporation would eventually have dried it out, but in 1928 Congress designated land below -220 feet as a repository for agricultural runoff. Through the 1970s, the lake's surface hovered at -227 feet, giving it an area of 378 square miles - the largest lake in California. Water from the Colorado, coming through the All-American Canal in the south and the Coachella Canal in the north, irrigated farmers' fields and then went into the Sea, maintaining its level. Today the sediment lining the shore contains pesticides and fertilizer from decades of runoff.

Egrets nest in two palm trees by an irrigation canal in the Imperial Valley. Water from irrigation eventually winds up in the Salton Sea. The Salton Sea is part of the Pacific Flyway, a resting place for millions of migratory birds.

The Salton Sea became a stopping point for more than 380 bird species migrating on the Pacific Flyway, including egrets, herons, gulls, eared grebes, white pelicans, Yuma clapper rails and gull-billed terns. The sea was stocked with fish species including corvina, sargo and bairdella. Tilapia introduced to control algae in irrigation canals also wound up in the lake.

Over the years the Salton Sea's salinity increased, however, from 3,500 parts per million to 52,000 ppm - about 50 percent saltier than the ocean. Fish, except the tilapia, died off. Phosphorus and nitrogen from fertilizers, and nutrients stirred up by winds from the sea's bottom, now create algae blooms that deplete oxygen, kill fish and contribute to diseases that kill birds. In 2012 the terrible stench from one algae bloom smothered Los Angeles for days, demonstrating that wind-borne dust may potentially travel that far as well. It can also blow south - across the border into Mexicali, Baja California's capital city of more than 650,000 people.

In 2003 California was forced to reduce the water it takes from the Colorado to legal limits. As a result of an agreement hammering out how it would be shared, water began to be transferred from the Imperial Valley to San Diego. California Rural Legal Assistance warned the state plan "fails to comply with the California Environmental Quality Act." At first valley growers agreed to fallow some fields, and the saved water continued to flow into the Sea. But this year fallowing ends, and water transfers to San Diego will rise sharply in December.

The California Natural Resources Agency says, "Inflow to the Salton Sea is expected to shrink significantly after 2017, when water transfers from the Imperial Valley accelerate and mitigation water deliveries stop under agreements reached years ago." The 2003 agreement said the state would pay to restore the environmental health of the Sea, but for 13 years no money was appropriated. Imperial County, its air pollution district and local growers tried to challenge the agreement in court, but lost.

The All-American Canal flows next to the U.S./Mexico border wall, and eventually ends at the Salton Sea.

According to a 2005 Border Asthma and Allergies (BASTA) Study conducted by the California Department of Public Health, 20.2% of children in Imperial County are diagnosed with asthma. The national average is 13.7%. Imperial County consistently has the highest asthma hospitalization rates among all California counties, and ten valley residents died of it from 2000 to 2004.

Not all asthma is due to dust from the Sea. Even smaller particles, called PM 2.5, come from smoke from burning fields after crops are picked. The Comite Civico has pushed for banning field burning for many years, but "it's cheaper for farmers to burn," says Humberto Lugo, a Comite Civico staff member. "There's no way to know exactly how much pollution is due to the Salton Sea. But we can say that peoples' problems are aggravated when the dust blows from the shoreline. My son in Calipatria [an Imperial Valley farmworker town very close to the shore] comes out to play baseball with a glove on one hand and his inhaler in the other. I can see this problem in my own family."

Calipatria, North Shore and the other towns around the sea are among the poorest in California. While California's unemployment rate is a about 5%, the Imperial County's rate is four times greater. Over 23% of the Imperial Valley's 177,000 residents (over 80% of whom are Latino) live in poverty.

"The wealth of the agricultural industry has been built on top of the suffering of generations of farm workers, from direct abuses in the fields to degradation of the land and environment," says Arturo Rodriguez, president of the United Farm Workers. "Nowhere are the hardships farm workers and their families endure more conspicuous today than with dust pollution from the Salton Sea. What good does it do farm workers to win better pay and benefits when their health is crippled because of where they live and work?"

Jaime Lopez applies an herbicide to weeds in a field of bell peppers at the edge of the Salton Sea. This method of applying the herbicide avoids using a spray that can damage the pepper plants and cause health problems for the workers. The herbicide will eventually be washed into runoff water, and into the sea.

Organizations like Comite Civico and the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability have pushed to put health concerns on the agenda for the state hearings about mitigating the impact of the water transfers. Over the last few years the Comite has put air monitors in over 40 sites, training community residents to understand their use. Many schools now fly flags when the monitors indicate dust storms or severe air contamination, warning students to stay indoors.

And for the first time, the state has budgeted $80 million for remediation, some of which goes to the Torrez Martinez tribe at the north end of the lake. They've begun creating new wetlands on their reservation, which lies next to the shoreline - some of it even under the water. The tribe's survival depends on rescuing their land. According to Alberto Ramirez, in charge of the project, "For the Torrez Martinez, there's nowhere else to go. What we have - this is it."

Of the tribe's 800 members only 300 still live on the reservation. Half of them have respiratory illness. "The most important reason for this project is recovering the health of the community," he adds.

Oral histories and songs preserve the Torrez Martinez' memories of earlier historical eras, in which water filled the basin and people would migrate from the lake's edge to the surrounding mountains and back. Now only five people speak their indigenous language, however. "But we have the ability to resist," explains Mike Mirelez, cultural resources director. "If we have better living conditions our tribe will become more self sufficient. With more resources we can set up after school programs for our kids, work towards revitalizing our language, and teach them how to grow food."

A project to build wetlands to remediate the rising dust from the receding shoreline of the Salton Sea - a project of the Torrez Martinez Indian tribe on their reservation.

Near the shoreline, the tribe's skiploaders move earth to create ponds for fish, and cascading pools and furrows to anchor native plants. They are creating a model. It only occupies a small part of an immense shoreline. To replicate it around the sea, and bring the water to make it thrive, would take not millions, but billions of dollars.

Ramirez believes that will be a long fight, "but we have to figure out how to adapt to survive, and the tribe has been doing this for generations." Comite Civico's Olmedo knows it will be a long fight too. "We should slow down the water transfer and make sure there's no water transfer without full mitigation," he urges. "Full mitigation means that there will be no new environmental exposure that threatens health. We have to keep the hazardous soil in the ground. San Diego should use all its available resources before pulling water from here. We should be an emergency resource, not a day to day water source."

According to Eduardo Garcia, the Imperial Valley's representative in the California State Assembly, "Our challenge is to cover up those [exposed] areas, to build habitat as fast as the sea recedes. That is the only option. The state's commitment is through a 10-year management plan to mitigate the public health impacts. It [$80 million] is enough to create a management plan, but it's not enough to restore the Salton Sea. We have to get the money we need to implement the rest of the plan. We're going to ask the Governor to fund the plan in its entirety. We need him to come through for us here in Imperial County. We need the money."

In the meantime, Maria Pozar and her children, and her neighbors in North Shore, have no plans to leave. "We're all poor people, living here because we work in the fields. My husband has a stable job and my whole family is here. We're going to spend our lives in North Shore. We can't move. Our kids are growing, and Jacqueline has all her friends here. I have a new baby. Now I wonder if he will have asthma too."

Ruben Sanchez is a beekeeper, working with hives next to a field near the U.S./Mexico border, south of the Salton Sea. He says that bees are under stress because of increased dust from the expanding shoreline. He has been a beekeeper for 21 years.

SIDEBAR: SIERRA CLUB'S "MY GENERATION" GIVES YOUTH A VOICE

Interview by David Bacon with Marina Barragan (MB), organizer of the My Generation campaign of the Sierra Club's San Gorgonio chapter, and two campaign activists, Christian Garza (CG) and his brother Ruben Garza (RG).

Christian Garza, Marina Barragan and Ruben Garza are activists in the Mi Generacion youth chapter of the Sierra Club. They often meet to talk about projects in the park in Mecca, a small farmworker town in the Coachella Valley near the Salton Sea. Christian has severe asthma from the dust in the air, and suffered a collapsed lung as a result.

CG - I was born with asthma. Last year there was a dust storm over a couple of days. I had an asthma attack and I went to school, but the two steroids I had with me wouldn't make it better. My mom picked me up and rushed me to the hospital. They called a code blue and told me I had a collapsed lung. If I'd been out there ten minutes longer my whole lung would have collapsed and I'd have suffocated.

The attacks used to be once a month - now it's every couple of days. And I'm only 19. What am I going to do when I'm 25? And I'm not the only kid with asthma here. There are so many kids with worse asthma than I have. In Mecca when the wind is building up the locals know that they should go inside. It becomes a ghost town. Just breathing it in is going to make you sick. You can't be out there for long

Eastern Coachella Valley's a low-income community and every time I'd have an asthma attack it would cost $200 in medication because I didn't have proper insurance. Then I would have to go down to the food bank because we couldn't afford any food after that. I always felt a huge burden. Even as a little kid I would lie to my mom, and tell her I didn't have an asthma attack, just because I knew there was not going to be food on the table after that.

RG - My mom sees the dust and thinks, 'Well what can we do about it?' She shouldn't have to worry that when we go outside we won't be ok when we come back in.

If you treat the Salton Sea just as a problem, you're treating my brother's asthma attacks as something he can just live with. But the Sea can be restored if we all put a hand out to each other. If we all work together we can provide water to keep the Sea from receding. Water in the Sea would give my brother a chance to live his life, a right every person should have. We need that water for people to live.

A ditch carries irrigation runoff from Coachella Valley fields and date orchards into the Salton Sea.

MB - The majority of the shoreline is on native reservation land. If it was in Sacramento or LA they would not have been able to ignore it for so long. But now there is an uproar in our community. People care here. The Sea is hurting a lot of people and yet it's a beautiful sea. We have to listen to the voices of the community and what they want for the Sea. The Sea is fighting to live and we're fighting with it. And we're not going to be chased out of our home because they can't clean it up.

A lot of people make it seem like it's the birds or public health. It doesn't have to be one or the other. It has to be both. My Generation is fighting for multi-purpose solutions that are beneficial for both public health and bird habitat. We need to get more water in the Sea create more wetlands - things that will happen now. The truth is we're here to save ourselves because if we let the sea die, we will die.

CG - I love this place, but it's hard to feel like I can have a family here and feel like they're safe. The Sierra Club showed me what caused my asthma attacks. I thought they were just normal, something I just had to live with. The Sierra Club gave me opportunities to get my voice out and let the people know what's happening to us. This is a chance for me to have some type of change for the better for me, my family, and my community.

MB - We need to be heard, that's the biggest thing. The My Generation campaign does grassroots organizing. We're trying to protect lives and marginalized communities like our own. But at the end of the day Christian still suffered a collapsed lung. My 4-year-old nephew developed asthma this year. My sister has asthma and bronchitis, and 10 years ago I lost my uncle to respiratory illness.

The three of us became family because we're fighting side by side for our lives. My Generation is not giving up.

A flag at Brawley High School, warning students of bad air quality and the need to stay indoors.

Sunday, December 17, 2017

Tuesday, December 5, 2017

END OF THE LEGAL LINE FOR GERAWAN FARMS

END OF THE LEGAL LINE FOR GERAWAN FARMS

By David Bacon

Capital and Main, 12/5/17

https://capitalandmain.com/end-of-the-legal-line-for-gerawan-farms-1204

Members of the United Farm Workers in San Francisco protest the case brought by Gerawan Farms in a demonstration in front of the State Supreme Court.

California's gigantic peach and grape grower, Gerawan Farms, reached the end of its legal road last week at the state Supreme Court, when justices unanimously threw out its claim that the company was not bound by the Mandatory Mediation Law, a provision of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA). In doing so, the court dealt a defeat to a cluster of right-wing think tanks, grower organizations and Republican politicians who sought to use the company's case to have the law itself declared unconstitutional, and to drastically weaken the collective bargaining rights of California farm workers.

"After four years of stalling," United Farm Workers president Arturo Rodriguez told Capital & Main, "Gerawan Farming Inc. should immediately honor the union contract hammered out by a neutral state mediator in 2013 and pay its workers the more than $10 million it already owes them."

The Gerawan case goes back a quarter of a century, to a union election held in 1990 and certified in 1992, when the company employed 1,000 workers. The election was marked by serious legal violations, and the Agricultural Labor Relations Board (ALRB) charged the company with tearing down housing for its workers among other efforts to intimidate them. Nevertheless, a majority of workers voted for the UFW.

The company challenged the election. After its appeal was rejected in 1995, the union asked to begin bargaining a contract to raise wages and provide benefits. In their one meeting, co-owner Mike Gerawan told union negotiators, "I don't want the union and I don't need the union." That ended bargaining.

In 2002, however, then-governor Gray Davis signed a bill to change that situation. Using this new section of ALRA, workers could vote for a union and later call in a mediator if their employer refuses to negotiate a first-time contract. The mediator, chosen by the state, hears from both the union and the grower, and writes a report recommending a settlement. Once the ALRB adopts the report, it becomes a binding union contract.

Growers challenged the law, taking it to the state Court of Appeals, where they lost in 2006. The union has since used mandatory mediation to negotiate contracts covering about 3,000 workers with several large California agricultural corporations, including D'Arrigo Brothers in Salinas and Triple E Produce in the San Joaquin Valley.

At Gerawan there was little union activity in the years following the company's refusal to negotiate, although the UFW says it maintained contact and relationships with the workers there. In 2012 the union sent the company another request to negotiate. A series of meetings were held, but agreement was never reached, so the UFW called for a mediator.

The mediator finally made a report to the ALRB, which adopted it in November, 2013. Under the law, that report should then have become the agreement. Gerawan, however, refused to implement it. Instead, by then it had already begun a multi-pronged campaign to avoid the contract and to challenge the law itself, including an aggressive campaign to get its employees to decertify their union. Gerawan benefited from the financial support of the Western Growers Association and the California Farm Bureau Federation. Its legal campaign was advised by the far-right Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence.

Inside the company, management organized a pro-company, anti-union group, which circulated the decertification petitions. Signatures were gathered by foremen, who canceled work shifts and pressured workers to attend pro-company rallies in Visalia and Sacramento. The rallies' expenses were borne by grower groups, including the California Fresh Fruit Association (formerly the Grape and Tree Fruit League). The Center for Worker Freedom, headquartered in the Washington DC offices of Grover Norquist's Americans for Tax Reform (ATR), publicized the pro-decertification demonstrations through, among other things, billboards in Sacramento attacking the UFW and ALRB. The ATR is funded by Karl Rove's Crossroads GPS and the Koch brothers, and its powerful political allies in the San Joaquin Valley include Republican Congressmembers Devin Nunes and Kevin McCarthy.

According to one worker, Jose Gonzalez, "When they passed around the decertification petitions, they looked at the crews who didn't sign them. Then those crews didn't have any more work." Severino Salas, another worker, says simply, "People were afraid to support the union, even though they wanted it, for fear of losing their jobs."

Under intense pressure from growers and their political allies, the ALRB scheduled a decertification election, despite pending charges of intimidation, company interference and even forged petition signatures. Before the ballots could be counted, however, board agents sealed the ballot boxes, saying no count could be made without hearings to determine if the election was free and fair. The charges were eventually upheld by the ALRB.

Gerawan's attorneys then convinced the State Court of Appeals for Fresno's conservative 5th District to rule in May, 2015, that the mandatory mediation section of the ALRA was unconstitutional. That decision, in which the court essentially ruled against its earlier decision validating the law, was appealed to the state Supreme Court. That tribunal finally decided the issue for good November 28.

In its argument, Gerawan claimed that its workers had been "abandoned" by the UFW during the years after the company refused to negotiate. The union's certification as the workers' bargaining agent, it therefore alleged, had expired sometime before the UFW made its 2012 renewed bargaining demand. Gerawan was joined by another grower making the same claim, Tri-Fanucchi Farms. The union and the ALRB argued that this abandonment idea would reward growers who could delay negotiating for years, replace their old pro-union workforces, and then claim the workers had been abandoned by the union. The state Supreme Court ruled specifically against this "abandonment" defense.

The Appeals Court had claimed in its 2015 decision knocking out the law that it would result in different standards for different employers. The Supreme Court also disagreed that this possibility was enough to invalidate the law.

Behind the legal arguments, however, lies ideology and economic self-interest. Gerawan opposes even the idea of unions and contracts for the 5,000 people who now pick its fruit. "We believe that coerced contracts are constitutionally at odds with free choice," Dan Gerawan said in an email to the Associated Press after the ruling. The company did not respond to Capital & Main's request for comment.

The UFW calculated that the difference between what those workers would have been paid under the mediator's 2013 union agreement, and what they were actually paid in the years since then, is about $10 million.

"Had the negotiations been successful many years ago you would have had years to deal with the union," noted Cruz Reynoso, a former California Supreme Court justice, in a letter to Gerawan in 2014. "What is troubling ... is that your refusal to implement the contract issued by the neutral mediator and the ALRB board means your workers continue to be denied the many millions of dollars in wage increases and other benefits they are already owed."

Now that the Supreme Court has essentially ordered Gerawan to implement the mediator's contract, the UFW will have to build a union at the company and enforce the agreement - no easy task given the years of Gerawan's anti-union campaign.

Meanwhile, membership in the UFW has been growing slowly in the past several years. The union has won representation elections and contracts in places like the Gourmet Trading blueberry farm, where a 2015 strike led to a contract covering about 450 pickers that was signed this past May. The Supreme Court decision itself won't likely lead to many new contracts based on past elections. But it will convince other growers that when workers vote for the union, the state has teeth that can force them to negotiate. That can encourage workers in other companies to organize, and to raise the abysmal wages now current in California agriculture.

Farm workers demonstrate in front of the State Supreme Court.

By David Bacon

Capital and Main, 12/5/17

https://capitalandmain.com/end-of-the-legal-line-for-gerawan-farms-1204

Members of the United Farm Workers in San Francisco protest the case brought by Gerawan Farms in a demonstration in front of the State Supreme Court.

California's gigantic peach and grape grower, Gerawan Farms, reached the end of its legal road last week at the state Supreme Court, when justices unanimously threw out its claim that the company was not bound by the Mandatory Mediation Law, a provision of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA). In doing so, the court dealt a defeat to a cluster of right-wing think tanks, grower organizations and Republican politicians who sought to use the company's case to have the law itself declared unconstitutional, and to drastically weaken the collective bargaining rights of California farm workers.

"After four years of stalling," United Farm Workers president Arturo Rodriguez told Capital & Main, "Gerawan Farming Inc. should immediately honor the union contract hammered out by a neutral state mediator in 2013 and pay its workers the more than $10 million it already owes them."

The Gerawan case goes back a quarter of a century, to a union election held in 1990 and certified in 1992, when the company employed 1,000 workers. The election was marked by serious legal violations, and the Agricultural Labor Relations Board (ALRB) charged the company with tearing down housing for its workers among other efforts to intimidate them. Nevertheless, a majority of workers voted for the UFW.

The company challenged the election. After its appeal was rejected in 1995, the union asked to begin bargaining a contract to raise wages and provide benefits. In their one meeting, co-owner Mike Gerawan told union negotiators, "I don't want the union and I don't need the union." That ended bargaining.

In 2002, however, then-governor Gray Davis signed a bill to change that situation. Using this new section of ALRA, workers could vote for a union and later call in a mediator if their employer refuses to negotiate a first-time contract. The mediator, chosen by the state, hears from both the union and the grower, and writes a report recommending a settlement. Once the ALRB adopts the report, it becomes a binding union contract.

Growers challenged the law, taking it to the state Court of Appeals, where they lost in 2006. The union has since used mandatory mediation to negotiate contracts covering about 3,000 workers with several large California agricultural corporations, including D'Arrigo Brothers in Salinas and Triple E Produce in the San Joaquin Valley.

At Gerawan there was little union activity in the years following the company's refusal to negotiate, although the UFW says it maintained contact and relationships with the workers there. In 2012 the union sent the company another request to negotiate. A series of meetings were held, but agreement was never reached, so the UFW called for a mediator.

The mediator finally made a report to the ALRB, which adopted it in November, 2013. Under the law, that report should then have become the agreement. Gerawan, however, refused to implement it. Instead, by then it had already begun a multi-pronged campaign to avoid the contract and to challenge the law itself, including an aggressive campaign to get its employees to decertify their union. Gerawan benefited from the financial support of the Western Growers Association and the California Farm Bureau Federation. Its legal campaign was advised by the far-right Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence.

Inside the company, management organized a pro-company, anti-union group, which circulated the decertification petitions. Signatures were gathered by foremen, who canceled work shifts and pressured workers to attend pro-company rallies in Visalia and Sacramento. The rallies' expenses were borne by grower groups, including the California Fresh Fruit Association (formerly the Grape and Tree Fruit League). The Center for Worker Freedom, headquartered in the Washington DC offices of Grover Norquist's Americans for Tax Reform (ATR), publicized the pro-decertification demonstrations through, among other things, billboards in Sacramento attacking the UFW and ALRB. The ATR is funded by Karl Rove's Crossroads GPS and the Koch brothers, and its powerful political allies in the San Joaquin Valley include Republican Congressmembers Devin Nunes and Kevin McCarthy.

According to one worker, Jose Gonzalez, "When they passed around the decertification petitions, they looked at the crews who didn't sign them. Then those crews didn't have any more work." Severino Salas, another worker, says simply, "People were afraid to support the union, even though they wanted it, for fear of losing their jobs."

Under intense pressure from growers and their political allies, the ALRB scheduled a decertification election, despite pending charges of intimidation, company interference and even forged petition signatures. Before the ballots could be counted, however, board agents sealed the ballot boxes, saying no count could be made without hearings to determine if the election was free and fair. The charges were eventually upheld by the ALRB.

Gerawan's attorneys then convinced the State Court of Appeals for Fresno's conservative 5th District to rule in May, 2015, that the mandatory mediation section of the ALRA was unconstitutional. That decision, in which the court essentially ruled against its earlier decision validating the law, was appealed to the state Supreme Court. That tribunal finally decided the issue for good November 28.

In its argument, Gerawan claimed that its workers had been "abandoned" by the UFW during the years after the company refused to negotiate. The union's certification as the workers' bargaining agent, it therefore alleged, had expired sometime before the UFW made its 2012 renewed bargaining demand. Gerawan was joined by another grower making the same claim, Tri-Fanucchi Farms. The union and the ALRB argued that this abandonment idea would reward growers who could delay negotiating for years, replace their old pro-union workforces, and then claim the workers had been abandoned by the union. The state Supreme Court ruled specifically against this "abandonment" defense.

The Appeals Court had claimed in its 2015 decision knocking out the law that it would result in different standards for different employers. The Supreme Court also disagreed that this possibility was enough to invalidate the law.

Behind the legal arguments, however, lies ideology and economic self-interest. Gerawan opposes even the idea of unions and contracts for the 5,000 people who now pick its fruit. "We believe that coerced contracts are constitutionally at odds with free choice," Dan Gerawan said in an email to the Associated Press after the ruling. The company did not respond to Capital & Main's request for comment.

The UFW calculated that the difference between what those workers would have been paid under the mediator's 2013 union agreement, and what they were actually paid in the years since then, is about $10 million.

"Had the negotiations been successful many years ago you would have had years to deal with the union," noted Cruz Reynoso, a former California Supreme Court justice, in a letter to Gerawan in 2014. "What is troubling ... is that your refusal to implement the contract issued by the neutral mediator and the ALRB board means your workers continue to be denied the many millions of dollars in wage increases and other benefits they are already owed."

Now that the Supreme Court has essentially ordered Gerawan to implement the mediator's contract, the UFW will have to build a union at the company and enforce the agreement - no easy task given the years of Gerawan's anti-union campaign.

Meanwhile, membership in the UFW has been growing slowly in the past several years. The union has won representation elections and contracts in places like the Gourmet Trading blueberry farm, where a 2015 strike led to a contract covering about 450 pickers that was signed this past May. The Supreme Court decision itself won't likely lead to many new contracts based on past elections. But it will convince other growers that when workers vote for the union, the state has teeth that can force them to negotiate. That can encourage workers in other companies to organize, and to raise the abysmal wages now current in California agriculture.

Farm workers demonstrate in front of the State Supreme Court.

Saturday, December 2, 2017

THE TRUE CONDITIONS OF FARM WORKERS TODAY

By David Bacon

The Progressive - 12/1/17

http://progressive.org/dispatches/in-the-fields-of-the-north-en-los-campos-del-norte/#prev

SAN DIEGO, CA - Just after arriving from Mexico, a Mixtec farm worker lives with her son in a tent on the hillside in Del Mar.

At the end of the 1970s California farm workers were the highest-paid in the U.S., with the possible exception of Hawaii's long-unionized sugar and pineapple workers. Today people are trapped in jobs that pay the minimum wage and often less, and mostly unable to find permanent year-around work.

In 1979 the United Farm Workers negotiated a contract with Sun World, a large citrus and grape grower. The contract's bottom wage rate was $5.25 per hour. At the time, the minimum wage was $2.90. If the same ratio existed today, with a state minimum of $10.50, farm workers would be earning the equivalent of $19.00 per hour.

Today farm workers don't make anywhere near $19.00 an hour. In 2008 demographer Rick Mines conducted a survey of 120,000 migrant farm workers in California from indigenous communities in Mexico - Mixtecos, Triquis, Purepechas and others -- counting the 45,000 children living with them, a total of 165,000 people. "One third of the workers earned above the minimum wage, one third reported earning exactly the minimum and one third reported earning below the minimum," he found.

In other words, growers were paying an illegal wage to tens of thousands of farm workers. The case log of California Rural Legal Assistance is an extensive history of battles to help workers reclaim illegal, and even unpaid, wages. Indigenous workers are the most recent immigrants in the state's farm labor workforce, and the poorest, but the situation isn't drastically different for others. The median income is $13,000 for an indigenous family, the median for most farm workers is about $19,000 - more, but still far from a liveable wage.

Low wages in the fields have brutal consequences. When the grape harvest starts in the eastern Coachella Valley, the parking lots of small markets in farm worker towns like Mecca are filled with workers sleeping in their cars. For Rafael Lopez, a farm worker from San Luis, Arizona, living in his van with his grandson, "the owners should provide a place to live since they depend on us to pick their crops. They should provide living quarters, at least something more comfortable than this."

In northern San Diego County, many strawberry pickers sleep out of doors on hillsides and in ravines. Each year the county sheriff clears out some of their encampments, but by next season workers have found others. As Romulo Muñoz Vasquez, living on a San Diego hillside, explains: "There isn't enough money to pay rent, food, transportation and still have money left to send to Mexico. I figured any spot under a tree would do."

Compounding the problem of low wages is the lack of work during the winter months. Workers have to save what they can while they have a job, to tide them over. In the strawberry towns of the Salinas Valley, the normal 10% unemployment rate doubles after the harvest ends in November. While some can collect unemployment, the estimated 53% who have no legal immigration status are barred from receiving benefits.

Yet people have strong community ties because of shared culture and language. Farm workers in California speak twenty-three languages, come from thirteen different Mexican states, and have rich cultures of music, dance, and food that bind their communities together. Migrant indigenous farmworkers participate in immigrant rights marches, and organize unions.

Indigenous migrants have created communities all along the northern road from Mexico to the U.S. and Canada. Migration is a complex economic and social process in which whole communities participate. Migration creates communities, which today pose challenging questions about the nature of citizenship in a globalized world. The function of these photographs, therefore, is to help break the mold that keeps us from seeing this reality.

The right to travel to seek work is a matter of survival for millions of people, and a new generation of photographers today documents the migrant-rights movements in both Mexico and the United States (with its parallels to the civil rights movement of past generations). Like many others in this movement, I use the combination of photographs and oral histories to connect words and voices to images - together they help capture a complex social reality as well as people's ideas for changing it.

Today racism is alive and well, and economic inequality is greater now than it has been for half a century. People are fighting for their survival. And it's happening here, not just in safely distant countries half a world away. As a union organizer, I helped people fight for their rights as immigrants and workers. I'm still doing that as a journalist and photographer. I believe documentary photographers stand on the side of social justice - we should be involved in the world and unafraid to try to change it.

FRESNO, CA - Raymundo Guzman and his partner, Miguel Villegas, do a rap number in Mixteco at a place in the fields outside of Fresno, where indigenous farmworkers get together to eat, drink and listen to the latest creations by the pair combining traditional culture with the music of the U.S. streets and barrios.

I'm going to be a rapper with a conscience - Raymundo Guzman

I was very young when my mother first took me to work in the fields -- about eight or ten years old. At first only she and my older brother were working. My brother would work with her, while the rest of us went to school. She took me to the fields so that I could start to learn, so that I would be ready when I was old enough to work.

It was just her and us kids, and she couldn't earn enough to support us all. She sold tamales and chicharrones, and tried to make money any way she could. In December she pruned trees. She was our mother and father. She had to look out for us. When there wasn't work in the fields she would kill a pig and make tamales, make mole and sew.

My memories of those times are good because I was working with my family and the people from my hometown. We all came from the same town in Oaxaca, San Miguel Cuevas. When I first arrived in Fresno I only spoke Mixteco. I had to learn Spanish to speak with other people in the street and in school.

I graduated from high school. I was the first in my family to do it. My mother was so proud that she threw me a party. It felt good to stand on stage and hear my name being called. I felt sad immediately afterwards, though, because I didn't know what to do with my diploma. It's like accomplishing something so big, and then everything comes crashing down. It's very depressing.

I was already working in the fields then, so I actually lost a day of work for graduation practice. I went to work in Oregon right after graduating, because I was saving up for a car. But the money seems to slip away. It's not much to begin with. The money you earn in a week goes to rent, food, gas and the cell phone bill.

I'm going to be a rap star. I think I'm going to be big, but I'm going to be a rapper with a conscience. My idol is Tupac Shakur. He spoke about politics and told the truth about all of us kids in poverty. He talked about our lives. It's like Tupac used to say, we're a flower that grew in concrete. You can see the rose and stem is twisted, but it grew out of the hard concrete. We're from the hood but we're going to come up. Some people may not want us to achieve much, but we're human too.

Rómulo Muñoz Vazquez

Here on the hillside - Rómulo Muñoz Vazquez

In San Pedro Muzuputla, the town I'm from, we're very poor, and I have four children. JThis is my second time coming to the United States, and I've been living in this encampment in San Diego for a year. When I first arrived I rented an apartment, but I couldn't make enough money to pay rent, food, transportation and still have money left to send to Mexico. I figured any spot under a tree would do, so I asked a coworker and he told me about this place. I bought some nylon and a tarp for the roof, and built my shack myself. My main goal is to save money and send it to my family.

We're outsiders. If we were natives here, then we'd probably have a home to live in. But we don't make enough to pay rent. We're poor and can't afford to go elsewhere.

Here in the camp very few speak Spanish. Most just speak their indigenous language. Those from Guerrero speak one language; the people from San Pedro Muzuputla speak another. We speak Amuzceñas. We don't understand Mixteco or Triqui -- it's very different. That's why it's good to speak Spanish.

When we aren't working, we're looking for work. Sometimes Americans stop by, and even though we only communicate by hand signals, they can tell us what job they want done. I was beaten at work five years ago, on a ranch by the freeway in San Diego. The boss asked us why we weren't working hard. I told him we weren't animals and we had rights. I still remember everything they did to me afterwards.

SAN DIEGO, CA - Jose Gonzalez, San Diego coordinator of the Binational Front of Indigenous Organizations, urges farm workers living on the Del Mar hillside to participate in the big immigrant rights march on May Day, 2006. Workers gather around the lunch truck at the bottom of the ravine below the camp to buy food or clothes, recharge cellphones and socialize with friends.

COACHELLA, CA -A crew of farm workers harvests romaine lettuce for Pamela Packing Company near Mecca, in the Coachella Valley. This crew cuts and packs the lettuce into boxes on the ground, the way lettuce harvesting was organized until the 1990s. This system gave lettuce workers control over the speed of the work and the amount cut. Growers replaced this work system in most places with lettuce machines, to end control of the harvest by workers.

MECCA, CA - Rafael and his grandson Ricardo Lopez work picking grapes in the Coachella Valley. They come from San Luis, Arizona, and live in their van in a parking lot in Mecca during the harvest. Ricardo says, "This is how I envisioned it would be working here with my grandpa and sleeping in the van. But it would be better if they put up apartments for us to live in. It's hot at night, and hard to sleep. There are a lot of mosquitoes, and the big lights are on all night. There are very few services here, and the bathrooms are very dirty. At night there are a lot of people here, coming and going. You never know what can happen, it's a bit dangerous. But my grandfather has a lot of experience and knows how to handle himself. I'm working here to save money for school. I look at how hard my grandfather has worked. He tells me to get an education, so I won't be in the situation he's in. I don't want to do field work for the rest of my life because it is very hard work and the pay is low. But I'm happy being here because I'm going to earn money."

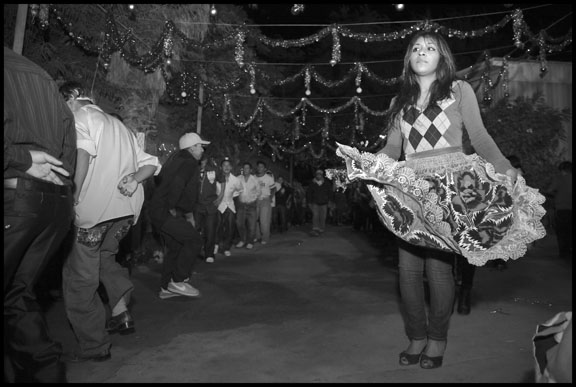

COACHELLA, CA - Members of the Purepecha community in the Coachella Valley gather at night to rehearse the Danza de Los Ancianos (the Dance of the Old People), preparing to perform it during a procession celebrating the Virgin de Guadalupe at Christmas. The rehearsal happens outdoors in the Chicanitas trailer camp.

TAFT, CA - Horacio Torres, a farm worker from Mexicali, tops onions late at night. Onion harvesters sometimes work at night, in order to get as many hours of work as possible, and also because of the heat during the day. Workers are not paid overtime wages for night work.

TAFT, CA - Ignacio Cruz Cruz, Marcelino Cruz Cruz, Francisca Santiago Bautista, Antonio Santiago Bautista, Teresa Santiago Gonzalez, Lourdes Cruz Santiago (baby), Jose Domingo Cruz Morales, and Antonio Cruz Morales. This extended family is part of a community of Mixtec farm workers from Oaxaca, who live in Taft.

REEDLEY, CA - Three Mexican farm workers share a small camp under the trees. They called it living "sin techo," or without a roof. Humberto comes from Zihuatanejo in Guerrero. Pedro, who wears an earring in his ear, comes from Hermosillo in Sonora. Ramiro comes from a tiny town in the Lancandon jungle of Chiapas, about halfway between Tapachula on the coast, and Palenque, the site of the Mayan ruins. None of the men has worked more than a few days in the last several months. The riteros (people with vans who give workers rides to the fields to work) won't pick them up, because they say they live with the vagabundos (vagabonds).

CHOWCHILLA, CA - Ana Lilia Avila, an immigrant from Acapulco, Guerrero, flirts with Heronimo Lopez, a Mixtec immigrant from San Juan Mixtepec, Oaxaca, while they work picking bell peppers. She used to work in restaurants in Acapulco, but didn't make enough to live on, so she came with her family to Fresno.

STOCKTON, CA - Angela Ruiz and Claudia Diaz are two lesbian farm workers who told their stories as part of Proyecto Poderoso, a project initiated by California Rural Legal Assistance, for ending discrimination against lesbian and gay farm workers in rural California.

HOLLISTER, CA - At the Hollister Public Library Triqui women dance to traditional music from their communities in Oaxaca. Hollister is another center of Triqui people in California.

SANTA MARIA, CA - Hieronyma Hernandez reaches for strawberries as she moves down a row, filling the plastic boxes that later appear on supermarket shelves.

BURLINGTON, WA - Outside the labor camp, the children of strikers at Sakuma Farms set up their own picket line on a fence at the gate. Their sign reads Justicia Para Todos - Justice for Everyone.

David Bacon's photographs and stories seek to capture the courage of people struggling for social and economic justice in the Philippines, Mexico and the United States. The text and photos are excerpted from his 2017 book, In the Fields of the North / En Los Campos del Norte, published simultaneously by the University of California Press in the U.S. and the Colegio de la Frontera Norte in Mexico.

Thursday, November 9, 2017

NAFTA, THE CROSS-BORDER DISASTER

NAFTA, THE CROSS-BORDER DISASTER

By David Bacon

The American Prospect, November 7, 2017

http://prospect.org/article/nafta-cross-border-disaster

By David Bacon

The American Prospect, November 7, 2017

http://prospect.org/article/nafta-cross-border-disaster

The border wall between California and Baja California, in the hills east of San Diego.

As the talks to renegotiate NAFTA unfold in Washington, most attention in the United States has understandably focused on its domestic impact. Yet the treaty also had an enormous effect on Mexico, spurring a wave of forced migration of millions of people. Today a growing number of union members in all three NAFTA countries believe the treaty should be renegotiated-first, just to heal the damage done to workers. But a new treaty, or a new relationship between Mexico, the U.S., and Canada, they say, should also ensure that a new NAFTA and other treaties like it never cause the same devastation.

Like the other trade agreements of our age, NAFTA is not really about trade. U.S. tariffs on Mexican imports were relatively low before it went into effect. In actuality, the treaty is an agreement to allow market penetration and investment, the relocation of production and the creation of supply chains in manufacturing. Up until the mid-1980s, Mexico had a very protective policy that restricted foreign investment and controlled the exchange rate to encourage domestic growth. A sharp shift in the late 1980s included market opening measures, privatization, and economic reforms. These reforms were accelerated by NAFTA's provisions on foreign investment.

The maquiladora industry had begun the movement of U.S. jobs to low-wage Mexican factories as far back as 1964. Today the original maquiladora program no longer exists, but the exceptions it established to Mexican and U.S. labor law and customs rules now apply through all of Mexico, and have spread into the U.S. as well.

NAFTA produced an increase in U.S. investment in auto plants, electronics and garment factories, meatpacking plants, and other enterprises. Foreign direct investment rose from $17 billion in 1994 to $104 billion in 2012. U.S. companies-not only in manufacturing-expanded into Mexico generally, using economic reforms and privatization as their wedge. Walmart became Mexico's largest private-sector employer. Union Pacific and Grupo Mexico bought up the nation's railroads and ended passenger service (which Union Pacific had long since ended in the U.S.).

Big Mexican capital also moved into the U.S., where Mexican investment last year reached $16 billion-the level of U.S. investment in Mexico in 1994, when NAFTA went into effect. A number of these corporations brought with them the anti-worker policies they had honed at home. Grupo Mexico, which began as the Mexican subsidiary of American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO), grew larger than the parent. Directed by the Larrea family, it bought out the U.S. stockholders, making it the owner of mines in Arizona and the Southwest, where it is now trying to enforce the same union-destroying cuts on U.S. miners that it imposed in in its Mexican mines, Cananea and Nacozari. El Super, a division of the Mexican Chedraui retail corporation, has become a large supermarket chain in southern California, fighting with the UFCW (the leading union of supermarket workers) and trying to operate as many stores without unions as it can.

These changes put Mexican workers increasingly into competition with U.S. and Canadian workers. At the time of its enactment, some NAFTA champions argued that it would reduce the wage differential between them. Though the wages of U.S. workers have largely stagnated, that differential has nonetheless grown. The average Mexican wage was 23 percent of the U.S. manufacturing wage in 1975. By 2002 it had fallen to less than 12 percent. NAFTA hurt Mexican wages, rather than reducing the differential. In the 20 years after NAFTA went into effect, the buying power of the Mexican minimum wage dropped by 24 percent.

A U.S. autoworker earns $21.50 an hour, and a Mexican autoworker $3, but a gallon of milk costs more in Mexico than it does here. It takes a Mexican autoworker over an hour's work to buy a pound of hamburger, while a worker in Detroit can buy it after 10 minutes. That doesn't mean that the Mexican workers are less productive: Mexican workers in the General Motors plant making the Sonic, Silverado, and Sierra produce the same number of cars per hour that the workers do in the U.S. plant making the same models. The difference means profit for GM, poverty for Mexican workers, and the migration from Mexico to the U.S. of those who can't survive.

The treaty forced yellow corn grown by Mexican farmers without subsidies to compete in Mexico's own market with corn from huge U.S. producers, subsidized by the U.S. farm bill. Corn imports rose from two million tons to more than ten million tons from 1992 to 2008. NAFTA prohibited price supports, without which hundreds of thousands of small farmers found it impossible to sell their corn or other farm products for what it cost to produce them. Mexico imported 30,000 tons of pork in 1995, and by 2010 that had grown to 811,000 tons, costing 120,000 jobs. The World Bank in 2005 found that the extreme rural poverty rate of 35 percent in 1992-94, prior to NAFTA taking effect, jumped to 55 percent in 1996-98, after NAFTA was in place. By 2010, 53 million Mexicans were living in poverty, about 20 percent in extreme poverty, almost all in rural areas.

Zacarias Salazar plows his cornfield in Juxtlahuaca, Oaxaca, behind oxen, in the traditional way with a wooden plow. Because of corn dumping enabled by the North American Free Trade Agreement, it is almost impossible for Salazar to grow and sell corn in Mexico any longer, and his crop is now mostly for the sustenance of his family.

In the agreement's first year, 1994, one million Mexicans lost their jobs, by the government's own count. According to Jeff Faux, founding director of the Economic Policy Institute, "the peso crash of December, 1994, was directly connected to NAFTA." And as the border maquiladora factories were tied to the U.S. market, Mexican workers lost jobs when the U.S. market shrank during recessions. In 2000-2001, at the time of the dot-com crash, 400,000 jobs were lost on the U.S./Mexico border, and in the Great Recession of 2008 thousands more were eliminated. With the border so close, many crossed it to survive.

NAFTA's purpose went beyond freeing investment. The treaty also produced displaced people, who then became the workforce in the maquiladoras and the fields of Baja California, and swelled an immense wave of migration to the U.S. and Canada. This was more than a foreseeable consequence of NAFTA-it was literally foreseen, and was as much a part of its purpose as the relocation of production.

In fact, Congress had been warned that NAFTA might increase poverty and fuel migration. When it passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) in 1986, Congress set up a Commission for the Study of International Migration and Cooperative Economic Development to study immigration's causes. Its report, delivered in 1990-three years before Congress ratified NAFTA-recommended negotiating a free trade agreement between the U.S, Mexico, and Canada. But it also warned, "It takes many years-even generations-for sustained growth to achieve the desired effect," and in the meantime would create years of "transitional costs in human suffering." Nevertheless, the negotiations that led to NAFTA started within months of the report's delivery.

People were migrating from Mexico to the U.S. long before NAFTA, but the treaty put migration on steroids. In 1990, 4.5 million Mexican migrants were living in the U.S. By 2008 the number reached 12.67 million-roughly 9 percent of Mexico's total population. Approximately 5.7 million of these immigrants were able to get some kind of visa, but another seven million couldn't, and came nevertheless.

The 1986 immigration reform act, which led to the negotiation of the free trade agreement, also re-established the bracero program, which had been abolished by the civil rights movement in 1965. Beginning in 1986, various categories of "guest worker" visas have been created, like the H2-A visa for agricultural workers. The Southern Poverty Law Center called these programs "close to slavery." In the last five years the number of H2-A workers recruited to come to the U.S. has risen from about 60,000 to 165,000 last year, and is predicted to reach 200,000 workers this year. That's 10 percent of the whole farm labor workforce, and in states like Washington, it's over a third. The laws that created this migratory workforce operate as a huge subsidy to U.S. agribusiness. U.S. employers don't have to pay the social cost of producing their workforce-the schools, health care, housing, or basic services in the Mexican towns from which the workers come. Instead, the burden falls on workers in the U.S. Mexican communities have become dependent on remittances by Mexican workers in the U.S., which totaled $27 billion in 2016. In 1996 they came to just $4 billion.

During the debate on NAFTA's original enactment, executives of companies belonging to USA•NAFTA, the agreement's corporate lobbyist, made extravagant claims that U.S. exports to Mexico would create 100,000 new jobs in the U.S. in its first year alone. Michael Wilson, director of the Heritage Foundation, predicted, "it will create an estimated 200,000 new jobs for Americans, reduce illegal immigration from Mexico, help tackle drug trafficking, strengthen Mexican democracy, and human rights, and serve as a model for the rest of the world." President Clinton claimed: "I believe that NAFTA will create 200,000 American jobs in the first two years." When he said "I believe that NAFTA will create a million jobs in the first five years," the claim was so extravagant that his press secretary had to walk it back the following day.

Clinton also promised that NAFTA would curtail the border crossings from Mexico. Speaking at the White House in September 1993, as the treaty was up for ratification in Congress, Clinton declared, "there will be less illegal immigration because more Mexicans will be able to support their children by staying home. This is a very important thing." At a time when the recession of the early '90s had devastated the Southern California economy in particular, Clinton's promises of reduced immigration played off voters' fears. Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari and his aides toured the U.S. for a year, also vowing that NAFTA would take pressure off U.S. workers. Full-page ads appeared in newspapers in which Citibank joined the chorus. In the end, the treaty was supported by almost all Republicans, joined by a minority of Democrats-just enough to ratify it.

If workers in the U.S. were worried about NAFTA's effect on their jobs, they had good reason to be. In the treaty's first decade the U.S. Department of Labor tracked of claims for unemployment benefits for workers who could show their employers had moved their jobs to Mexico. When the total passed 500,000, however, President George W. Bush ordered the Department of Labor to stop counting. "By 2010, trade deficits with Mexico had eliminated 682,900 good U.S. jobs, most (60.8 percent) in manufacturing," according to Robert E. Scott of the Economic Policy Institute. "Jobs making cars, electronics, apparel and other goods moved to Mexico, and job losses piled up in the United States, especially in the Midwest where those products used to be made."

Detroit lost half its population as the auto industry left, and today every engine in a Ford comes from Mexico. Huge swaths of other industrial cities have also taken on that abandoned look that comes with boarded-up homes and storefronts. But the working families who lost those outsourced jobs didn't disappear. Instead, hundreds of thousands of people began an internal migration within the U.S. larger than the dustbowl displacement of the 1930s. Former machinists and factory workers went on the road, landing low-wage jobs in fast food restaurants or Walmarts. Many lost their families. Some began living on the streets.

Job losses had a particular impact on workers of color. Plants that freeze broccoli and strawberries for frozen food companies like Green Giant moved from Watsonville to Irapuato. That cost the jobs of thousands of women who'd come north from Mexico, and then spent years on the freezer lines in Watsonville. In auto and other manufacturing plants, African American workers had long since broken the color line into more skilled and better paying jobs, only to see them relocated and the plants close.

Employers bent on lowering wages or canceling health care plans quickly learned to use NAFTA to inspire that fear. In 1997 Cornell professor Kate Bronfenbrenner found that one out of every ten employers facing a union drive told their workers they'd move to Mexico if the employees voted in a union. In 2009 a second Bronfenbrenner report, "No Holds Barred," found that 57 percent of employers facing a union election threatened to close their worksite. According to Jeff Faux, "NAFTA strengthened the ability of U.S. employers to force workers to accept lower wages and benefits."

When NAFTA had come before Congress, its supporters argued that any race to the bottom by corporations determined to lower labor costs or violate workers' rights could be blocked by the so-called labor protections in a side-agreement to NAFTA-the North American Agreement on Labor Cooperation. This made NAFTA more politically palatable for those Democrats in Congress who wanted to ratify the treaty anyway.

The record of the side agreement is dismal. In its most recent status report, the Department of Labor lists the 37 cases-24 against Mexico, 13 against the U.S., and two against Canada-that have been brought under the agreement in the quarter century since NAFTA's passage. Almost all against Mexico concerned violations of the right to freedom of association, to strike and to bargain. Cases against the U.S. involved violations of union rights and the rights of immigrant workers. The two cases against Canada concerned violations of the right to collective bargaining.

The most any union or group of workers ever got from filing a case was "consultations" between the governments, and public hearings. There is no provision in the agreement for assessing penalties for violation of union rights. There are minor penalties for violating child labor or occupational health laws, but they've never been invoked. Not a single union contract was signed as a result of the side-agreement process, nor was a single worker rehired. Those unions that have filed cases have generally sought to use the process to gain public exposure of abuses, and exert indirect pressure on employers.

Silvestre Reyes, a striker at the Han Young maquiladora. Many unions from southern California sent delegations to Tijuana to support the workers in their effort to set up an independent union. But when the strikers went to a meeting called by the Mexican government as a result of a labor side agreement complaint, to advise workers of their right to an independent union, the strikers were beaten up in the ballroom of Tijuana's prestigious Camino Real Hotel.

Was this just a flaw in the enforcement mechanism or something deeper? The purpose of NAFTA and other trade agreements has been to open economies for corporate investment, using lower labor costs as incentives to attract investment. It is unrealistic to expect that a side agreement to enforce already weak labor laws could mitigate the treaty's fundamental purpose.

Despite its corporate tilt, however, NAFTA did produce a new relationship among unions and workers in all three countries. Many working people in the United States, especially if they belonged to unions that campaigned against NAFTA, started to open their eyes about the real conditions of their fellow workers in Mexico, and could see how those conditions encouraged employers to relocate their jobs. In response, workers and a number of progressive unions on both sides of the border have come closer together.

When the Mexican government, for instance, tried to change Mexico's labor law, or passed corporate-backed education reform, or began to privatize the electrical and oil industries, U.S. unions have joined with Mexican unions to fight these changes. Many U.S. unions today understand that the impact will be felt in the displacement of Mexican workers and their migration to the United States and Canada, in the pressure their own workers will feel to accept concessions, or in the closure of plants and workplaces.

Even before the treaty passed, activists in all three countries set up networks like the Border Committee of Women Workers, the Coalition for Justice in the Maquiladoras, Enlace and the Workers' Support Center. The United Steelworkers became the crucial support base for Mexican miners in their eight-year strike in Cananea, one of the world's largest copper mines, and gave sanctuary to the union's leader, Napoleon Gomez Urrutia, when he was forced to leave Mexico. The United Electrical Workers and Mexico's Authentic Workers Front developed a permanent strategic alliance, assisting in each other's organizing drives.

This kind of cross-border cooperation and solidarity is now a fact of life in the labor movements of all three countries-a consequence the authors of NAFTA certainly did not intend.

The debates around the treaty, which came at the same time as the breakup of the Soviet Union, also helped spell the death knell of the U.S. labor movement's Cold War support for free-trade policies and its opposition to other nations' more radical unions. Over the past two decades, the labor movement has been moving towards new principles of solidarity with other nations' unions.

NAFTA had an equally great impact in changing U.S. labor's way of looking at immigration and immigrant workers. In 1986 the AFL-CIO supported IRCA, the immigration reform legislation that made it illegal for undocumented workers to hold a job. But the wave of immigration that NAFTA produced changed the demographics of many U.S. workplaces, and with it, the demographics of U.S. unions. Not only did the number of immigrant workers increase, but over the years they took on a growing role in organizing unions in many industries, and eventually, in the leadership of those unions themselves.

At the same time, U.S. unions saw immigration law and policy used against them. In Washington state 1000 apple pickers were fired when they tried to join the Teamsters, and in Nebraska 3000 meatpacking workers, many of whom either belonged to unions or were trying to organize unions in their plants, were driven from their jobs. In some cases their employers called in the federal immigration agents, but in others the Federal government itself demanded massive firings. In consequence, in 1999, the AFL-CIO changed its official position on immigration policy, calling for an end to the deportation and firing of undocumented workers, for legalizing people without papers, and for a trade policy that doesn't produce poverty and displacement.

Today the AFL-CIO's statement on NAFTA renegotiation declares that, "all workers, regardless of sector, have the right to receive wages sufficient for them to afford ... a decent standard of living." The federation would prohibit the export of products made by companies paying less. Progressive Mexican unions and community organizations support this, because it would give workers and farmers a future without having to leave their homes in search of a living wage.

On the other hand, the Mexican government now argues that Mexican wages must stay low to attract investment, and has accused independent unions there of betraying the national interest by seeking to raise them. With its presidential election coming next year, that position may well doom its ruling political party, not just to unpopularity, but to massive rejection at the polls. Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, a past leftwing candidate now leading in the polls, has condemned the policy of using low wages to attract investment, and called for an economy based on producing jobs and social services that would give Mexicans a future in Mexico.

The basis of labor solidarity is in many ways stronger today than it was in 1994, but labor is still playing a catch-up game. Border workers have gone on strike in four Juarez maquiladoras and the fields of San Quintin in recent years, and in Cananea and the Rio Sonora valley miners are still on strike after nearly a decade. In the U.S., where millions of workers are very aware, and fearful, about the loss of their jobs because of NAFTA and globalization, unions have yet to convince many people that solidarity, not hatred of Mexicans or of immigrants, is the real answer to their desperation.

But when unions began to respond to NAFTA in 1993 and 1994, they knew they were in for a fight, yet they believed that change was possible nonetheless. It still is. Facing one of the most labor-hostile U.S. governments in decades, and trade proposals likely to undermine their strength even further, unions can still be a standard bearer for workers in all three countries.

Monday, November 6, 2017

BERLIN EXHIBITION - EXPOSICION EN ALEMANIA - THE BORDER, THE WORK AND THE FIGHT FOR JUSTICE

BERLIN EXHIBITION - THE BORDER, THE WORK AND THE FIGHT FOR JUSTICE

EXPOSICION EN ALEMANIA - LA FRONTERA, EL TRABAJO Y LA LUCHA POR LA JUSTICIA

EXPOSICION EN ALEMANIA - LA FRONTERA, EL TRABAJO Y LA LUCHA POR LA JUSTICIA

Sunday, October 29, 2017

THE ART OF THE BORDER: LOOKING FOR KIKITO

THE ART OF THE BORDER: LOOKING FOR KIKITO

By David Bacon

Capital and Main, The American Prospect, 10/26/17

https://capitalandmain.com/the-art-of-the-border-searching-for-kikito-1026

http://prospect.org/

A man on the Mexican side of the border wall between Mexico and the U.S. looks through the bars, where the wall runs into the Pacific Ocean.

For almost an hour Laura, Moises and I drove through the dusty neighborhoods of Tecate, looking for Kikito. Tecate is a small city in the dry hills of Baja California, next to the U.S. border. It's famous for a huge brewery, although today most workers find jobs in local maquiladoras.

When we asked for directions, a couple of people had heard of Kikito, but couldn't tell us where he was. Most didn't know who we were talking about.

We figured that if we kept driving along the border fence we'd find him. On the hot empty streets not much was moving. In these neighborhoods the second storeys of large comfortable homes, mostly built in the 40s and 50s, rise above adobe walls enclosing their courtyards. But unlike downtown, with its colorful bustle, there was no street life out here, hardly anyone on the sidewalk.

Finally we passed the one man who could surely tell us how to find Kikito - the cable guy. He even volunteered to lead us in his van part of the way. Using his directions, we bumped along a dirt road next to the border fence, up and down a couple of hills where the city fades into scrubland. Then we found Kikito.

He was much larger than I'd imagined.

The "Kikito" art installation at the U.S. Mexico border wall, created by French artist JR. From the U.S. side it seems the child is grabbing the wall and looking over it to the U.S. side. From the Mexican side it is impossible for Mexicans to see it in this way. Laura Velasco stands on a little hill near the structure, giving an idea of it huge size.

Kikito is an enormous photograph of a one-year old child, pasted onto cut-out plywood sheets. The assemblage is mounted on a huge, complex metal scaffold, about 65 feet high, much like what painters erect to embrace the buildings they work on. Kikito's scaffolding, however, doesn't embrace anything. Instead, it pushes the enormous photograph towards, and above, the border wall's severe vertical iron bars.

The structure is so big that to bring the photo into position, part of the hillside had to be excavated, and a hole dug deep into the ravine at the bottom. A few walled houses in the distance line the rim of the hill above.

I felt like Dorothy going behind the curtain, when she suddenly confronts the Wizard as he manically pulls levers to present his fierce, disembodied face to the audience out in front. Like the Wizard's, you can only see Kikito's visage the right way from the other side of the curtain - in this case, the metal fence separating Tecate from the U.S.

Viewed rom the U.S. side, Kikito becomes an enormous black and white toddler, his chubby hands appearing to grip the top of the border wall as he seems to look over it, into the mysterious United States. He has a slight smile.

If we'd been on the U.S. side, driving east from San Diego, we could have followed the directions Kikito's creator, the French artist JR, posted on his website. There you can even see JR's photograph of two U.S. Border Patrol agents staring at the baby. Apparently they often help visitors find the right spot.

We now have 20,000 Border Patrol agents, whose parked vans dot the desert all along the border wall from California to Texas, as they wait to grab someone trying to cross. Helping visitors find Kikito must provide a welcome break in the tedium of watching and waiting, sitting in sweaty vans on shadeless hills, where the temperature climbs to 105 degrees and above.

At this spot along the border wall between Mexico and the U.S., Border Patrol agents fired through the wall, and killed Ramses Barron-Torres. His portrait and a cross are on the wall of the building in Mexico below, where he fell. Agents say they were justified in shooting because people were throwing stones at them, but the street is far below and there is little danger that a stone could even pass through the iron bars at such a distance.

It's obvious that Kikito's audience is located in the U.S. "The piece is best viewed from the U.S. side of the border," JR's website explains. In fact, the optical illusion can only be seen from that side - Mexicans standing in Tecate, where it's actually located, can't see it the right way. JR says Kikito is looking "playfully," but then admits, "Kikito and his family cannot cross the border to see the artwork from the ideal vantage point."

I took a photo of Laura on a nearby hummock, just to give an idea of the structure's immense scale. She seems diminutive next to it. In her classes at the Colegio de la Frontera Norte (COLEF) in Tijuana, and in her books and research about the migration of Mexico's indigenous people to Baja California and eventually to the U.S., Laura Velasco is hardly dispassionate. She advocates for migrants, and has no love for the wall and its unsubtle messages of "Keep Out!" and "Stay in Mexico!"

That's one reason she liked Kikito. "He shows us to be human beings," she said, looking up at his half smile. "That's a good message for people in the U.S. And he does it without shouting, just by being who he is." If people in Mexico can't see him properly, she thinks, they're not the ones who need to get the message anyway.

When the installation went up, President Trump had just issued his threat to terminate the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA ) program, withdrawing the legal status of 800,000 young people brought by their parents to the U.S. without visas as children. Many of those youth - the Dreamers - saw a baby looking over the border wall as a symbol of their own humanity in the face of fear and possible deportation.

Yet my visceral reaction, as I looked down the hillside at this immense toddler, was more skeptical. In a desert where hundreds of people die every year of thirst and exhaustion, trying to dodge Border Patrol agents, trekking on foot across the wall in the intense heat, is it enough to simply say, "Immigrants are human beings"? Why such a soft message in such a harsh context?

Migrants found dead on the border between the U.S. and Mexico, in the area of the Imperial Valley and Colorado River, are buried in a potters field graveyard in Holtville. The identities of many are not known, and are buried as "John Doe" or "Jane Doe." Immigrant rights and religious activists have made crosses for many of the graves, most of which say "No Olvidados" or "Not Forgotten."

The wall, and the border militarization of which it is a part, is exacting a terrible cost. It's paid by uprooted Oaxacan farmers needing work and money to send home, by parents and children desperate to reunite families fractured by earlier migrations, by Honduran refugees fleeing violence. When many die crossing the desert (232 in the first seven months of 2017), they're buried in the Holtville cemetery, 89 miles east of Kikito in the Imperial Valley.

Successive U.S. administrations beef up the Border Patrol's numbers, build multiple walls, hand out contracts for high-tech surveillance devices, detain hundreds of thousands of people in for-profit detention centers, and then deport them. In President Trump's election rallies crowds chanted, "Build the Wall!"

It's a big media story, and produces a fascination with the border among U.S. photographers and artists, who then create photodocumentaries and art projects currently popular in the mainstream media. The border sells, in other words. Kikito is part of a growing genre.

Richard Misrach, a well-known photographer, produced a large book of photographs, Border Cantos, which shows the absurdity of a wall of iron bars that suddenly stops at a golf course, allowing real estate agents to play through. He communicates an atmosphere of violence in images of spent shells on the range where Border Patrol agents practice shooting, and the possibility of death from thirst in images of flags signaling the water cans left by immigration activists and Good Samaritans along the migrant trails. But like Kikito, his audience is in the U.S. The photographs, almost all without people, look at the border wall from that northern side.

Some projects are less documentary. In the New Yorker , writer Jonathan Blitzer recounts that Magnum photographer Carolyn Drake "set out for the U.S.-Mexico border just after Donald Trump won the Presidency."