GUEST WORKERS ON FARMS STAND IN THE EYE OF THE COVID STORM

By David Bacon

Capital & Main, 4/30/20

https://capitalandmain.com/guest-workers-on-farms-are-in-the-eye-of-the-covid-storm-0430

Carlos Gutierrez, an immigrant H-2A guest worker, strings up wire supports for planting apple trees in Washington state. (Photo by David Bacon)

No to family immigration, but yes to guest workers

On April 21 President Trump announced in a tweet that, while stopping almost all kinds of legal immigration for at least two months, he was placing no limits on the continued recruitment of H-2A guest workers by growers. Trump claimed the spreading COVID-19 pandemic made his order necessary, but he cited no evidence to show that a ban covering all forms of family-based migration would stop the virus' spread, while leaving employer-based migration unchanged would not exacerbate the pandemic.

Trump has repeatedly declared his support for the guest worker program. In a 2018 Michigan speech he told a grower audience, "We're going to let your guest workers come in, because we have to have strong borders, but we have to let your workers in ... They're going to work on your farms ... but then they have to go out. But we're gonna let them in because you need them ... We have to have them."

Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue explained the apparent contradiction. He wants Trump "to separate immigration, which is people wanting to become citizens, [from] a temporary, legal guest-worker program. That's what agriculture needs, and that's what we want. It doesn't offend people who are anti-immigrant because they don't want more immigrant citizens here. We need people who can help U.S. agriculture meet the production."

This promise is more than election-year politics. It is a big step towards creating a captive workforce in agriculture, based on a program notorious for abuse of the workers in it, and for placing them into low-wage competition with farmworkers already living in the U.S.

It is also a step into the past. Family preference migration, in which immigrants can get residence visas (green cards) based on their family relationships, was won by the civil rights movement. Bert Corona, Cesar Chavez and others convinced Congress to end the bracero program in 1964. They fought for an immigration policy based on family unification, instead of one based on growers' desire for a low-wage labor supply.

Especially for immigrants coming from Asia, Africa and Latin America, this new system made it possible to unite families in the U.S., settle down and become part of communities. Before that watershed step, people could come from Mexico to work as braceros, but not to stay, and not with families. Immigration quotas favoring white migration from Europe made it very hard for families in general to come from non-European countries.

When President Trump said, in a 2018 meeting with Senator Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), "Why do we want these people from all these shithole countries here? We should have more people from places like Norway," he was voicing his nostalgia for that pre-civil rights past.

Trump has now suspended the family preference system. Whether it will be reinstated at some point is anyone's guess. And the H-2A program, which is growing rapidly, is a direct descendant of the old bracero regime. It will continue, given its support in a Congress that is much more conservative than the one in 1964, which abolished the bracero program and established the family migration system. Even Democrats in the current Congress have introduced legislation that would greatly expand H-2A.

Although growers have claimed the coronavirus has created a labor shortage making the H-2A program vital, the program was mushrooming long before the pandemic hit. Last year the U.S. Department of Labor gave agribusiness permission to fill 257,667 jobs with workers brought almost entirely from Mexico, with H-2A visas. That amounted to 10 percent of all the jobs in U.S. agriculture.

The program is five times bigger than the 48,336 jobs certified under George W. Bush in 2005. In some states H-2A certifications now make up more than 10 percent of farmworker jobs. In Georgia growers fill a quarter of all farm labor jobs with H-2A workers.

An agricultural system in which half the workforce would eventually consist of H2-A workers is not unlikely. Florida, Georgia, and Washington are already heading in this direction. Rosalinda Guillen, director of Community to Community, a farmworker advocacy organization in Bellingham, Washington, charges that this expansion "shifts agriculture in the wrong direction, which will lead to the eventual replacement of domestic workers and create even more of a crisis than currently exists for their families and communities."

The problem with H-2A

H-2A workers are given contracts for less than one year, they can only work for the company that contracts them, and they must leave the country at the end of the contract. If they protest abusive conditions they can be fired and deported. And because they must reapply to come back for the following season, they are uniquely vulnerable to blacklisting.

Investigators from the Centro de los Derechos de Migrante (the Migrant Rights Center, CDM) reported in a detailed study released in March, "Ripe for Reform," that "many believed that they would not be allowed to return to work in the U.S. at all if they did not complete a contract, regardless of the reason."

One large recruiter, CSI Visa Processing, with 12 offices in Mexico, brings more than 25,000 workers to the U.S. every year. It has them sign a pledge that authorizes a blacklist: "The boss has the right to fire me and I ... will have to go back to Mexico, and the boss will report me to the authorities. This will obviously affect my ability to return legally to the United States in the future."

"The vast majority of workers start their H-2A jobs deeply in debt," the CDM reported, some paying bribes as much as $4,500, despite legal prohibitions on such "fees." They are often housed in barracks on the grower's property, miles from the nearest town, surrounded by barbed wire fences. "Some workers stated that they needed permission to leave the housing. Others indicated they were prohibited from leaving other than to buy groceries," the CDM study found.

One worker, Mario, said he was charged $1,000 a month for a bunk bed in a barrack with 30 to 40 other workers. When some workers tried to leave, the boss illegally took their passports. "They didn't want us to leave or go anywhere," Mario said.

All interviewees in the CDM report suffered violations of basic labor laws, including receiving wages less than the minimum for H-2A workers and the denial of required breaks. Eighty-six percent reported that companies wouldn't hire women or paid them less when they did. Half complained of bad housing, and a third said they were not provided needed safety equipment. Forty-three percent were not paid the wages promised in their contracts.

"Fraud and misrepresentation about wages were very common," according to the CDM.

One worker reported getting paid $1.25 per hour after illegal kickbacks. Another got $400 for a seven-day week, working 11 hours a day. Underpayment over the lifetime of his contract was $11,000. Multiplied by the dozens of workers in an average crew picking fruit or harvesting vegetables gives an idea of the illegal profits available to employers who seemingly have little fear of consequences.

That lack of fear is understandable given the virtual absence of enforcement. In 2019, out of 11,472 employers using the H-2A program, the Department of Labor filed cases against only 431 (3.73 percent), and of them only 26 (0.25 percent) were barred from recruiting for three years, with an average fine of $109,098.

After one H-2A worker, Honesto Silva, collapsed in a field in Washington State three years ago, and later died, 70 of his co-workers refused to go into the fields. The company, Sarbanand Farms, fired them, and threw them out of the labor camp. Because the H-2A regulations require workers to leave the country if they are terminated, firing effectively meant deporting them.

Washington's new union for farmworkers, Familias Unidas por la Justicia, supported that protest and others by H-2A workers - in 2018 at Crystal View farm and in 2019 at the King Fuji apple ranch. According to Edgar Franks, organizer for Familias Unidas, most of the workers who participated in the Crystal View and King Fuji strikes were not working for the company in the following season.

Favors for growers, COVID for workers

Since his election, Trump has continually tried to make the H-2A program more accessible and profitable for growers. Earlier this year the government dropped a restriction to allow growers to recruit only workers who'd been recruited in the past. Then it suspended a regulation barring growers from keeping workers in the U.S. beyond the end of their old contracts.

Another promised rule change would relax the requirement that companies advertise jobs first to local residents before applying for H-2As. The most important promise was to cut the wage that growers must pay H-2A workers, the Adverse Effect Wage Rate. Set high enough, in theory, not to undermine the prevailing wages of local farmworkers, it actually puts a ceiling on them. If local workers demand wage increases, growers can hire H-2A workers instead.

Low wages put enormous pressure on all farmworkers to go to work, even during the coronavirus crisis. Farmworker families are among the poorest in the U.S., with an average annual income between $17,500 and $20,000-below the official poverty line. Increasing that pressure during the COVID-19 crisis is the fact that half of the country's 2.5 million farmworkers-those without legal status-were written out of all the relief programs passed by Congress. A quarter of a million H-2A workers were written out of the relief bills as well.

The coronavirus crisis adds risk to inequality. Like everyone, H-2A workers must try to maintain the recommended six feet of distance between people in housing, transportation and working conditions. But the CDM report concludes: "That will be impossible under conditions H-2A workers typically experience in the United States." There is no testing for them as they enter the country nor while they're here.

Employers are not required to provide health insurance to H-2A workers. If they stop working because they get sick, the conditions of their visa require them to leave the country. Once in Mexico they then have to find medical care, while their families and communities face the danger of infection.

Uncomfortably close

As Congress began discussing bailout and relief packages in March, however, unions and community organizations began drafting proposals and demands. Thirty-six groups signed a letter drafted by the Washington, D.C. advocates Farmworker Justice, calling for more protections for H-2A workers. Recommendations include safe housing with quarantining facilities, safe transportation, testing of workers before entering the U.S., social distancing at work, and paid treatment for those who get sick. In Washington State Columbia Legal Services filed suit, together with the United Farm Workers, Familias Unidas por la Justicia and Community2Community, a farmworker organizing project, to force the state to set health standards for H-2A workers.

The H-2A program, as changed by the administration, will not likely revert to its pre-pandemic state, however. And H-2A regulations were clearly ineffective in protecting workers before the crisis. Fourteen years ago conditions of H-2A workers were described in a report by the Southern Poverty Law Center, "Close to Slavery." CDM counsel Mary Bauer, who authored that report, charges, "I haven't seen any significant improvement in 30 years. Abuse is baked into a structure in which workers are vulnerable, and where there's always a new supply of workers to replace the old, the sick or those who complain and protest. A program that gives workers virtually no bargaining power creates a perfect storm of vulnerability in the context of this pandemic."

The CDM report makes the same point. "The problem with protecting workers merely by promulgating regulations," it emphasizes, "is that regulations cannot overcome the profound power imbalance between employer and worker."

In the 1960s the Chicano civil rights movement campaigned not to regulate guest worker programs, but to abolish them. Activists fought for an immigration system based on family unification instead. That is the change President Trump now wants to reverse with a tweet.

Thursday, April 30, 2020

Wednesday, April 8, 2020

WAR AND OCCUPATION OPENED THE DOOR TO IRAQ'S VIRUS PANDEMIC

WAR AND OCCUPATION OPENED THE DOOR TO IRAQ'S VIRUS PANDEMIC

To fight COVID-19, Iraqi workers want political change

By David Bacon

The Nation, 4/8/20

https://www.thenation.com/article/world/iraq-coronavirus-pandemic/

Union leader Falah Alwan, president of the Federation of Workers Councils and Unions of Iraq, and leather goods factory workers argue with the plant manager about their union rights in 2003.

Solidarity, Then the Virus

Many U.S. union activists remember Falah Alwan. As the occupation of Iraq unfolded in the summer of 2005, he and several Iraqi union leaders traveled here to make clear the impact of sanctions and invasion on his country's workers. From one union hall to another, on both coasts and through the Midwest, Alwan and his colleagues appealed for solidarity.

In the end, the war's damage went virtually unhealed, but the ties forged between workers and unions of the two countries have remained undiminished. Last week, as both face the coronavirus pandemic, Alwan wrote to the friends he made in those years. "The news from New York is horrible," he commiserated. "I believe the days to come will be much worse than they are now, not only in Iraq but for you also."

In 2005 the Iraqis effectively dramatized the human cost of U.S. policy. Today, as both countries face the coronavirus, the devastating situation of Iraq's people calls for revisiting that question of responsibility.

On paper, the virus’s toll in Iraq today stands at 1,031 officially confirmed cases, with 64 deaths. While Iraq's per capita count is still much smaller than that in the U.S. - 22 cases per million people to the U.S.' 910 - the numbers don't tell the real story. In Iraq very few people can access medical treatment, and the number of infections and deaths is much higher than that given in official statements.

This past week Reuters reported that confirmed cases numbered instead between 3000 and 9000, quoting doctors and a health official - a report that led the Iraqi government to fine the agency and revoke its reporting license for three months. The higher figure would give Iraq a per capita infection rate higher than South Korea, one of the virus' early concentrations.

Unions and civil society organizations must now try to make up for Iraq's political paralysis and the partial dysfunction of its government. "Because of our ruined healthcare institutions," Alwan explains, "the government hurried to impose a general curfew [a stay-at-home order] to stop the outbreak and a rapid collapse in the whole situation."

That had an enormous impact, especially on workers. Public employees encompass 40% of the workforce, and in theory should still be receiving salaries. But Hashmeya Alsaadawe, head of the country's union for electricity workers and Iraq's highest-ranking woman union leader, points out that eighty thousand of her members have already gone without wages for months because of the country's economic crisis. Yet they are expected, and do, show up for work to provide essential services. In oil refineries and state-owned factories it's the same situation - essential and unpaid - one of the reasons for the huge demonstrations that have challenged the government since last October.

Hashmeya Alsaadawe, President of the Electricity and Energy Union in Basra and the Basra Federation of Trade Unions in 2005, the first woman to be elected as a national trade union leader in Iraq's history.

In the meantime, to stop people from moving within the country, "the main roads were barricaded by concrete blocks," she says. "While this is necessary, the government did not provide anything for those who earn their living on a daily basis. Shops and markets simply closed."

"There's not even a promise of pay for workers losing jobs in the private sector," Alwan adds. "And more than seven million Iraqis only have informal work. To survive, they're obliged to violate the curfew, especially in the slums where three million live in Baghdad alone. Authorities have detained more than 7000 people there, and fined more than 3000 in Najaf." Iraq's population is about 40 million.

How War and Sanctions Destroyed Iraq's Healthcare System

Economic desperation contributes to the impact of the virus, but another factor makes it much more lethal. The spread of COVID-19 is taking place in a country with a devastated healthcare system. The U.S. owns a great part of the responsibility for this. Two invasions, a decade of sanctions and the occupation largely caused the ruin of Iraq's medical and public health systems.

According to an analysis by the Enabling Peace in Iraq Center, "Before the imposition of international sanctions in 1991, Baghdad operated some of the most professional and technologically advanced healthcare and public health institutions in the Arab world." The Ministry of Health operated 172 modern hospitals, 1200 primary care centers and 850 community clinics, providing free healthcare with an annual budget of $450 million. While the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s produced enormous casualties, the infrastructure itself was not attacked.

Public health depends on well-functioning water and sanitation systems, which served 90 percent of the population in the 1970s. They were destroyed by U.S. bombing in the first Gulf War in 1991. The EPIC report noted, "By March the Tigris River was 'running thickly and slowly with human waste,' according to a Baghdad University law professor. An 87-member international monitoring committee reported that in Iraq’s 30 largest cities, electricity, water, and sewage services were close to total collapse ... Deliberate targeting of civil infrastructure by US airstrikes, and enduring UN sanctions ... dissolved the foundations on which Iraq’s medical infrastructure was built." In the 2003 invasion, 7% of Iraq's remaining hospitals were destroyed and 12% looted in the subsequent chaos.

Over a third of the country's 52,000 licensed physicians fled during the sanctions period of the 1990s. Then another 18,000, over half of those who had remained, left during the extreme violence that followed the U.S. occupation. That violence especially affected healthcare workers. Omar Dewachi, a professor at Brown University, says Baghdad's hospitals were "transformed into ‘killing fields.’” By 2012 Iraq had a third of the doctors, per capita, of Jordan, Syria or even the Israeli-occupied territories.

Apartment buildings built by the government for working class residents of Basra. There is no room here for people with the virus to self-isolate

In the occupation's first six years the U.S. did budget $13.4 billion to rebuild the healthcare system, through the Iraq Relief and Recovery Fund. The fund and U.S. reconstruction projects were marked by fraud and theft, however, leading Senator Robert Byrd (D-W VA) to charge in 2008, “Tens of billions of taxpayer dollars are lost, … gone! ... Individuals think they can get away with bilking—they’re not just milking—bilking the U.S. and Iraqi governments… taking bribes, substituting inferior workmanship, or plain, old-fashioned stealing! Stealing!”

Privatization and Cuts

Instead of rebuilding the healthcare system and basic infrastructure, the occupation introduced private ownership. Now Iraq has a two-track system in which basic services are provided by the Ministry of Health, although they're no longer free. Sami Adnan, an activist in Workers Against Sectarianism, which helped organize the protests that began last October, charges, "Today we have to pay for every single visit and often, in order to get treatment, we are obliged to give a bribe to the few remaining doctors in the country.”

Iraqis - with money - can buy treatment at the Andalus Hospital and Specialized Cancer Treatment Center, a 140,000 square-foot hospital on the eastern side of Baghdad. Owned by mogul Rafee al-Rawi, it boasts a mammography machine, PET and CT scanners, an MRI machine, and even an 8300-ton cyclotron to manufacture a rare anti-cancer medicine. Or they can simply get treatment in another country with a better healthcare system. Both alternatives are subsidized by the government. Or they can pay for drugs smuggled into the country. Forty percent of those limited drugs available are brought in illegally, after merchants pay bribes of $30,000 per container.

Iraq's old State Company for Drugs Industries used to manufacture 300 drugs, and now makes only half that. “We used to export to Eastern European and Arab states. Now look at us,” says Mudhafar Abbas, a manager at the State Company for Marketing Drugs and Medical Appliances.

Driving the decline is a sharp cut in the money the Iraqi government budgets for healthcare, to just 2.5% of $106.5 billion, a much lower rate than the countries around it. The military, by contrast, gets 18% of expenditures, and the oil industry 13%. Even healthcare's small appropriation is now in danger. "A catastrophic economic situation is sweeping the whole country," Alwan warns, "because the budget was calculated when oil's price per barrel was $56, and it is now $24 [recently rising to $34 - ed]. Oil revenue makes up 90% of the budget, so officials plan to cut salaries, and the exchange rate of the Iraqi dinar to the dollar. Millions of workers, especially in the public sector, will pay for this."

The head of the Parliamentary Human Rights Committee, Deputy Arshad al-Salhi warned that even before the virus Iraqis were suffering from a lack of food and miserable wages. He urged the Ministry of Health to provide for families below the poverty line and the unemployed. "This strategy must be worked out by the competent authorities immediately, otherwise we are going towards a famine," al-Salhi said.

Iraq's current prime minister designate, Adnan al-Zorfi, announced a program at the end of March to create a crisis committee, enact measures to detain the virus' spread, provide food to those who need it, and ask for international assistance. The government would provide an "appropriate budget to provide for the requirements." Where the money would come from, no ne knows. He then called on social groups outside the government to help provide aid.

In the aftermath of the 2003 invasion tank treads and turrets were piled in the middle of a residential neighborhood. The wreckage included depleted uranium ammunition, a big health hazard to residents, dissolved in a pond of toxic waste next to apartment buildings.

The Iraqi administration has demanded that private corporations who operate oil concessions keep producing during the crisis. But selling pumping concessions to the world's petroleum behemoths, rather than operating the oil fields on a nationalized basis as it did before the occupation, means the government has only limited control. Some companies continue to keep the oil and dollars flowing, but at least one, the Malaysian giant Petronas, closed down its field and sent its workers home in fear of the pandemic.

The Oil Ministry could ramp up production in its state-operated fields, but must depend on the willingness of oil workers. Their union, the Iraqi Federation of Oil Workers, is the most powerful in the country. It, along with other unions, strongly backed the protests rocking Iraq since last fall. Those huge confrontations in the streets led to the resignation of al-Zorfi's predecessor, Muhammad Tawfiq Allawi, and his predecessor, Adel Abdul Mahdi.

A Wave of Protest Demanding Change

Beginning during the Arab Spring of 2009, waves of demonstrators have occupied Baghdad's Tahrir Square, with smaller protests in Basra and other cities. Hundreds of thousands of Iraqis have risked confrontation with troops and armed militias to condemn the failure of the government to provide jobs, clean water and healthcare. Infuriating especially are the electrical failures, providing no more than a few hours of power each day in the blistering summer.

In 2018 Iraqi Communists joined forces with cleric Moqtada al-Sadr, hoping to harness the power of the protests in their Sairoon electoral coalition. They campaigned against corruption and patronage that divides government posts according to religion. While Iraqi unions don't have a formal endorsement process for candidates, Sairoon clearly had the support of many, if not most union members. It won a plurality of votes in a multi-party system, but not enough seats in Parliament to form a government.

Last year the demonstrations surged again. In September hundreds of doctors filled Baghdad streets, demanding bigger budgets for healthcare, and better pay and security for medical workers. In October thousands of young people came out in every major Iraqi city. And on October 29 the Iraqi military fired on them, killing hundreds in Baghdad, while paramilitaries murdered 18 in Karbala. In Tahrir Square young doctors tried to bandage wounds and provide emergency triage care.

The oil workers were deeply involved. “We stand in solidarity with the demonstrations against corrupt rule in Iraq," their statement said. "The Iraqi people of all classes stand together as one to demand their rights. These rights have been taken away by an unjust government that uses violence, including sniper fire, against defenseless people who have nothing but their faith in God and in the justice of their cause.” In southern Iraq, where the oil and container terminals are located, union members shut down the ports.

In a prescient criticism, unions condemned the Iraqi government for growing completely dependent on oil income, making the country vulnerable to price shifts, while neglecting agriculture and manufacturing, important parts of earlier economic development. From October to March the demonstrations continued. By then, according to the Independent High Commission for Human Rights, the death toll had reached 566, ten times the virus deaths so far, while the number of injured topped 17,000.

In Baghdad people depend for transportation on a network of crowded vans, which make it difficult to maintain social distancing. The curfew now makes travel like this virtually impossible.

Labor and Grassroots Respond to the Virus

Then COVID-19 hit. And while many of those camped out in Tahrir Square left, not all did. Some remained, and began forming teams to go into neighborhoods and talk about the health crisis. The Iraqi Students Union set up a special medical unit to give basic examinations. For these activists, demonstrating against the government and working to overcome the virus are connected.

Sami Adnan says, "the reasons why we took to the streets in recent months were precisely these: the social and health system is totally insufficient to meet people's needs. Inside our tent village in Tahrir Square we are disinfecting everything: clothes, tents, mattresses, blankets, tools and utensils. We are distributing personal protective equipment such as masks and gloves."

Iraqi journalist LuJain Elbaldawi agrees: "The situation in Iraq is heading toward a comprehensive health crisis that the government is unable to cope with; thus, has resorted to drawing from civil society institutions, religious organizations and charities."

At first many clerics, including Moqtada al-Sadr, urged people to continue to come to the mosque and attend religious events. Planes continued to arrive with pilgrims from Iran, where the virus is raging. After pleas from health authorities, however, the imams reversed their earlier edicts. Some went further. In Karbala the al-Abbas shrine built a hall with 52 rooms for infected people. Mullah Hussein al-Awsi in Baghdad told the Al-Monitor news website, “We have formed teams of commission members to disinfect public spaces such as shops, public markets, sports arenas and some of the residential neighborhoods that are difficult for the government to reach.”

Grassroots groups and individuals responded as well. In Baghdad mobile bakeries travel through neighborhoods, distributing bread so that residents don't have to leave home. As people are doing all over the world, activist Nadia Mohammed in Kirkuk began making and handing out facemasks to those with no money to buy them.

Hashmeya Alsaadawe, who is also president of the Basra Trade Union Federation, says the ability of her union to provide aid is limited by the fact that "the government does not recognize our legitimacy nor the legitimacy of other unions." This denial dates back to the Saddam Hussein dictatorship, when the government prohibited unions in the public sector, including oil, electricity and the state enterprises that still dominate the economy.

Workers on an oil drilling rig in the South Rumaila oil field outside of Basra, in southern Iraq in 2005. Workers still go to work to produce the oil since the economy would stop immediately if they didn't.

While that outright prohibition was ended in a 2016 reform, withholding recognition keeps unions from collecting dues and functioning normally. "Our financial capabilities, therefore, are almost zero," she says, "so we're able to provide needed support only to poor workers. We distribute donations and food baskets where we can, and in addition we educate all workers through social media about the dangers of this virus and how to prevent it."

Under union pressure the government has made changes in some workplaces, by only having half of the workforce on the job at one time. In others the shifts have been lengthened in order to increase the number of days off. But, Alsaadawe says, the rules can change in each department and enterprise. "Changes were also too slow, and didn't take into account the seriousness of this virus. Some workplaces only distributed sanitizers in a few departments. Workers who labor crowded together were not released, nor were masks and gloves distributed to them. Individuals had to get them for themselves."

Political Demands

Many unions have gone beyond trying to protect their own members, and call for holding the government responsible for its failures. A National Program of Action to Combat the Coronavirus begins by declaring that "The authorities underestimated the experience of the countries of the world, and did not lift a finger to respond to the crisis until the middle of March."

The declaration, circulated by Hassan Juma'a Awad, president of the Iraqi Federation of Oil Workers, does not stop there. "The cause of the spread of this virus is the capitalist system in the first place," it charges, "and its continuous quest to accumulate capital and profits at the expense of the health and life of people."

The IFOW then lists an extensive set of demands, many echoing those put forward by unions and progressive organizations in the U.S.. The government "must provide drugs and supplies to those who need them," it begins, "with immediate testing, starting with health workers on the front lines," as well as prioritizing people with chronic health problems.

Medicine and food should be rationed and their prices controlled, with meals provided at schools. The government must "pay the wages of all workers, public and private for 4 months and throughout the quarantine period, including payments for those disabled and unemployed and the old and retired." Meanwhile there should be a moratorium on payment of rents, loans, water and electricity bills, and taxes.

To prevent the virus from spreading, people in prisons and detention centers should be released "so that prisons don't turn into epidemics." Public events must be halted, including religious ones, and the border closed to pilgrims from Iran and other pandemic-stricken countries.

Given Iraq's huge protests and wrenching political changes over the last year, unions clearly see that the important long term response is political. By formulating demands for the whole population, not just for workers and union members, the call reaches out beyond labor to "all socialist and human-friendly forces, parties, organizations, labor and women's and professional associations and movements calling for equality." Ultimately, it holds Iraq's economic system responsible for the crisis, and demands basic political change to deal with it.

Hassan Juma'a Awad, President of the Iraqi Federation of Oil Workers, in 2005.

To fight COVID-19, Iraqi workers want political change

By David Bacon

The Nation, 4/8/20

https://www.thenation.com/article/world/iraq-coronavirus-pandemic/

Union leader Falah Alwan, president of the Federation of Workers Councils and Unions of Iraq, and leather goods factory workers argue with the plant manager about their union rights in 2003.

Solidarity, Then the Virus

Many U.S. union activists remember Falah Alwan. As the occupation of Iraq unfolded in the summer of 2005, he and several Iraqi union leaders traveled here to make clear the impact of sanctions and invasion on his country's workers. From one union hall to another, on both coasts and through the Midwest, Alwan and his colleagues appealed for solidarity.

In the end, the war's damage went virtually unhealed, but the ties forged between workers and unions of the two countries have remained undiminished. Last week, as both face the coronavirus pandemic, Alwan wrote to the friends he made in those years. "The news from New York is horrible," he commiserated. "I believe the days to come will be much worse than they are now, not only in Iraq but for you also."

In 2005 the Iraqis effectively dramatized the human cost of U.S. policy. Today, as both countries face the coronavirus, the devastating situation of Iraq's people calls for revisiting that question of responsibility.

On paper, the virus’s toll in Iraq today stands at 1,031 officially confirmed cases, with 64 deaths. While Iraq's per capita count is still much smaller than that in the U.S. - 22 cases per million people to the U.S.' 910 - the numbers don't tell the real story. In Iraq very few people can access medical treatment, and the number of infections and deaths is much higher than that given in official statements.

This past week Reuters reported that confirmed cases numbered instead between 3000 and 9000, quoting doctors and a health official - a report that led the Iraqi government to fine the agency and revoke its reporting license for three months. The higher figure would give Iraq a per capita infection rate higher than South Korea, one of the virus' early concentrations.

Unions and civil society organizations must now try to make up for Iraq's political paralysis and the partial dysfunction of its government. "Because of our ruined healthcare institutions," Alwan explains, "the government hurried to impose a general curfew [a stay-at-home order] to stop the outbreak and a rapid collapse in the whole situation."

That had an enormous impact, especially on workers. Public employees encompass 40% of the workforce, and in theory should still be receiving salaries. But Hashmeya Alsaadawe, head of the country's union for electricity workers and Iraq's highest-ranking woman union leader, points out that eighty thousand of her members have already gone without wages for months because of the country's economic crisis. Yet they are expected, and do, show up for work to provide essential services. In oil refineries and state-owned factories it's the same situation - essential and unpaid - one of the reasons for the huge demonstrations that have challenged the government since last October.

Hashmeya Alsaadawe, President of the Electricity and Energy Union in Basra and the Basra Federation of Trade Unions in 2005, the first woman to be elected as a national trade union leader in Iraq's history.

In the meantime, to stop people from moving within the country, "the main roads were barricaded by concrete blocks," she says. "While this is necessary, the government did not provide anything for those who earn their living on a daily basis. Shops and markets simply closed."

"There's not even a promise of pay for workers losing jobs in the private sector," Alwan adds. "And more than seven million Iraqis only have informal work. To survive, they're obliged to violate the curfew, especially in the slums where three million live in Baghdad alone. Authorities have detained more than 7000 people there, and fined more than 3000 in Najaf." Iraq's population is about 40 million.

How War and Sanctions Destroyed Iraq's Healthcare System

Economic desperation contributes to the impact of the virus, but another factor makes it much more lethal. The spread of COVID-19 is taking place in a country with a devastated healthcare system. The U.S. owns a great part of the responsibility for this. Two invasions, a decade of sanctions and the occupation largely caused the ruin of Iraq's medical and public health systems.

According to an analysis by the Enabling Peace in Iraq Center, "Before the imposition of international sanctions in 1991, Baghdad operated some of the most professional and technologically advanced healthcare and public health institutions in the Arab world." The Ministry of Health operated 172 modern hospitals, 1200 primary care centers and 850 community clinics, providing free healthcare with an annual budget of $450 million. While the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s produced enormous casualties, the infrastructure itself was not attacked.

Public health depends on well-functioning water and sanitation systems, which served 90 percent of the population in the 1970s. They were destroyed by U.S. bombing in the first Gulf War in 1991. The EPIC report noted, "By March the Tigris River was 'running thickly and slowly with human waste,' according to a Baghdad University law professor. An 87-member international monitoring committee reported that in Iraq’s 30 largest cities, electricity, water, and sewage services were close to total collapse ... Deliberate targeting of civil infrastructure by US airstrikes, and enduring UN sanctions ... dissolved the foundations on which Iraq’s medical infrastructure was built." In the 2003 invasion, 7% of Iraq's remaining hospitals were destroyed and 12% looted in the subsequent chaos.

Over a third of the country's 52,000 licensed physicians fled during the sanctions period of the 1990s. Then another 18,000, over half of those who had remained, left during the extreme violence that followed the U.S. occupation. That violence especially affected healthcare workers. Omar Dewachi, a professor at Brown University, says Baghdad's hospitals were "transformed into ‘killing fields.’” By 2012 Iraq had a third of the doctors, per capita, of Jordan, Syria or even the Israeli-occupied territories.

Apartment buildings built by the government for working class residents of Basra. There is no room here for people with the virus to self-isolate

In the occupation's first six years the U.S. did budget $13.4 billion to rebuild the healthcare system, through the Iraq Relief and Recovery Fund. The fund and U.S. reconstruction projects were marked by fraud and theft, however, leading Senator Robert Byrd (D-W VA) to charge in 2008, “Tens of billions of taxpayer dollars are lost, … gone! ... Individuals think they can get away with bilking—they’re not just milking—bilking the U.S. and Iraqi governments… taking bribes, substituting inferior workmanship, or plain, old-fashioned stealing! Stealing!”

Privatization and Cuts

Instead of rebuilding the healthcare system and basic infrastructure, the occupation introduced private ownership. Now Iraq has a two-track system in which basic services are provided by the Ministry of Health, although they're no longer free. Sami Adnan, an activist in Workers Against Sectarianism, which helped organize the protests that began last October, charges, "Today we have to pay for every single visit and often, in order to get treatment, we are obliged to give a bribe to the few remaining doctors in the country.”

Iraqis - with money - can buy treatment at the Andalus Hospital and Specialized Cancer Treatment Center, a 140,000 square-foot hospital on the eastern side of Baghdad. Owned by mogul Rafee al-Rawi, it boasts a mammography machine, PET and CT scanners, an MRI machine, and even an 8300-ton cyclotron to manufacture a rare anti-cancer medicine. Or they can simply get treatment in another country with a better healthcare system. Both alternatives are subsidized by the government. Or they can pay for drugs smuggled into the country. Forty percent of those limited drugs available are brought in illegally, after merchants pay bribes of $30,000 per container.

Iraq's old State Company for Drugs Industries used to manufacture 300 drugs, and now makes only half that. “We used to export to Eastern European and Arab states. Now look at us,” says Mudhafar Abbas, a manager at the State Company for Marketing Drugs and Medical Appliances.

Driving the decline is a sharp cut in the money the Iraqi government budgets for healthcare, to just 2.5% of $106.5 billion, a much lower rate than the countries around it. The military, by contrast, gets 18% of expenditures, and the oil industry 13%. Even healthcare's small appropriation is now in danger. "A catastrophic economic situation is sweeping the whole country," Alwan warns, "because the budget was calculated when oil's price per barrel was $56, and it is now $24 [recently rising to $34 - ed]. Oil revenue makes up 90% of the budget, so officials plan to cut salaries, and the exchange rate of the Iraqi dinar to the dollar. Millions of workers, especially in the public sector, will pay for this."

The head of the Parliamentary Human Rights Committee, Deputy Arshad al-Salhi warned that even before the virus Iraqis were suffering from a lack of food and miserable wages. He urged the Ministry of Health to provide for families below the poverty line and the unemployed. "This strategy must be worked out by the competent authorities immediately, otherwise we are going towards a famine," al-Salhi said.

Iraq's current prime minister designate, Adnan al-Zorfi, announced a program at the end of March to create a crisis committee, enact measures to detain the virus' spread, provide food to those who need it, and ask for international assistance. The government would provide an "appropriate budget to provide for the requirements." Where the money would come from, no ne knows. He then called on social groups outside the government to help provide aid.

In the aftermath of the 2003 invasion tank treads and turrets were piled in the middle of a residential neighborhood. The wreckage included depleted uranium ammunition, a big health hazard to residents, dissolved in a pond of toxic waste next to apartment buildings.

The Iraqi administration has demanded that private corporations who operate oil concessions keep producing during the crisis. But selling pumping concessions to the world's petroleum behemoths, rather than operating the oil fields on a nationalized basis as it did before the occupation, means the government has only limited control. Some companies continue to keep the oil and dollars flowing, but at least one, the Malaysian giant Petronas, closed down its field and sent its workers home in fear of the pandemic.

The Oil Ministry could ramp up production in its state-operated fields, but must depend on the willingness of oil workers. Their union, the Iraqi Federation of Oil Workers, is the most powerful in the country. It, along with other unions, strongly backed the protests rocking Iraq since last fall. Those huge confrontations in the streets led to the resignation of al-Zorfi's predecessor, Muhammad Tawfiq Allawi, and his predecessor, Adel Abdul Mahdi.

A Wave of Protest Demanding Change

Beginning during the Arab Spring of 2009, waves of demonstrators have occupied Baghdad's Tahrir Square, with smaller protests in Basra and other cities. Hundreds of thousands of Iraqis have risked confrontation with troops and armed militias to condemn the failure of the government to provide jobs, clean water and healthcare. Infuriating especially are the electrical failures, providing no more than a few hours of power each day in the blistering summer.

In 2018 Iraqi Communists joined forces with cleric Moqtada al-Sadr, hoping to harness the power of the protests in their Sairoon electoral coalition. They campaigned against corruption and patronage that divides government posts according to religion. While Iraqi unions don't have a formal endorsement process for candidates, Sairoon clearly had the support of many, if not most union members. It won a plurality of votes in a multi-party system, but not enough seats in Parliament to form a government.

Last year the demonstrations surged again. In September hundreds of doctors filled Baghdad streets, demanding bigger budgets for healthcare, and better pay and security for medical workers. In October thousands of young people came out in every major Iraqi city. And on October 29 the Iraqi military fired on them, killing hundreds in Baghdad, while paramilitaries murdered 18 in Karbala. In Tahrir Square young doctors tried to bandage wounds and provide emergency triage care.

The oil workers were deeply involved. “We stand in solidarity with the demonstrations against corrupt rule in Iraq," their statement said. "The Iraqi people of all classes stand together as one to demand their rights. These rights have been taken away by an unjust government that uses violence, including sniper fire, against defenseless people who have nothing but their faith in God and in the justice of their cause.” In southern Iraq, where the oil and container terminals are located, union members shut down the ports.

In a prescient criticism, unions condemned the Iraqi government for growing completely dependent on oil income, making the country vulnerable to price shifts, while neglecting agriculture and manufacturing, important parts of earlier economic development. From October to March the demonstrations continued. By then, according to the Independent High Commission for Human Rights, the death toll had reached 566, ten times the virus deaths so far, while the number of injured topped 17,000.

In Baghdad people depend for transportation on a network of crowded vans, which make it difficult to maintain social distancing. The curfew now makes travel like this virtually impossible.

Labor and Grassroots Respond to the Virus

Then COVID-19 hit. And while many of those camped out in Tahrir Square left, not all did. Some remained, and began forming teams to go into neighborhoods and talk about the health crisis. The Iraqi Students Union set up a special medical unit to give basic examinations. For these activists, demonstrating against the government and working to overcome the virus are connected.

Sami Adnan says, "the reasons why we took to the streets in recent months were precisely these: the social and health system is totally insufficient to meet people's needs. Inside our tent village in Tahrir Square we are disinfecting everything: clothes, tents, mattresses, blankets, tools and utensils. We are distributing personal protective equipment such as masks and gloves."

Iraqi journalist LuJain Elbaldawi agrees: "The situation in Iraq is heading toward a comprehensive health crisis that the government is unable to cope with; thus, has resorted to drawing from civil society institutions, religious organizations and charities."

At first many clerics, including Moqtada al-Sadr, urged people to continue to come to the mosque and attend religious events. Planes continued to arrive with pilgrims from Iran, where the virus is raging. After pleas from health authorities, however, the imams reversed their earlier edicts. Some went further. In Karbala the al-Abbas shrine built a hall with 52 rooms for infected people. Mullah Hussein al-Awsi in Baghdad told the Al-Monitor news website, “We have formed teams of commission members to disinfect public spaces such as shops, public markets, sports arenas and some of the residential neighborhoods that are difficult for the government to reach.”

Grassroots groups and individuals responded as well. In Baghdad mobile bakeries travel through neighborhoods, distributing bread so that residents don't have to leave home. As people are doing all over the world, activist Nadia Mohammed in Kirkuk began making and handing out facemasks to those with no money to buy them.

Hashmeya Alsaadawe, who is also president of the Basra Trade Union Federation, says the ability of her union to provide aid is limited by the fact that "the government does not recognize our legitimacy nor the legitimacy of other unions." This denial dates back to the Saddam Hussein dictatorship, when the government prohibited unions in the public sector, including oil, electricity and the state enterprises that still dominate the economy.

Workers on an oil drilling rig in the South Rumaila oil field outside of Basra, in southern Iraq in 2005. Workers still go to work to produce the oil since the economy would stop immediately if they didn't.

While that outright prohibition was ended in a 2016 reform, withholding recognition keeps unions from collecting dues and functioning normally. "Our financial capabilities, therefore, are almost zero," she says, "so we're able to provide needed support only to poor workers. We distribute donations and food baskets where we can, and in addition we educate all workers through social media about the dangers of this virus and how to prevent it."

Under union pressure the government has made changes in some workplaces, by only having half of the workforce on the job at one time. In others the shifts have been lengthened in order to increase the number of days off. But, Alsaadawe says, the rules can change in each department and enterprise. "Changes were also too slow, and didn't take into account the seriousness of this virus. Some workplaces only distributed sanitizers in a few departments. Workers who labor crowded together were not released, nor were masks and gloves distributed to them. Individuals had to get them for themselves."

Political Demands

Many unions have gone beyond trying to protect their own members, and call for holding the government responsible for its failures. A National Program of Action to Combat the Coronavirus begins by declaring that "The authorities underestimated the experience of the countries of the world, and did not lift a finger to respond to the crisis until the middle of March."

The declaration, circulated by Hassan Juma'a Awad, president of the Iraqi Federation of Oil Workers, does not stop there. "The cause of the spread of this virus is the capitalist system in the first place," it charges, "and its continuous quest to accumulate capital and profits at the expense of the health and life of people."

The IFOW then lists an extensive set of demands, many echoing those put forward by unions and progressive organizations in the U.S.. The government "must provide drugs and supplies to those who need them," it begins, "with immediate testing, starting with health workers on the front lines," as well as prioritizing people with chronic health problems.

Medicine and food should be rationed and their prices controlled, with meals provided at schools. The government must "pay the wages of all workers, public and private for 4 months and throughout the quarantine period, including payments for those disabled and unemployed and the old and retired." Meanwhile there should be a moratorium on payment of rents, loans, water and electricity bills, and taxes.

To prevent the virus from spreading, people in prisons and detention centers should be released "so that prisons don't turn into epidemics." Public events must be halted, including religious ones, and the border closed to pilgrims from Iran and other pandemic-stricken countries.

Given Iraq's huge protests and wrenching political changes over the last year, unions clearly see that the important long term response is political. By formulating demands for the whole population, not just for workers and union members, the call reaches out beyond labor to "all socialist and human-friendly forces, parties, organizations, labor and women's and professional associations and movements calling for equality." Ultimately, it holds Iraq's economic system responsible for the crisis, and demands basic political change to deal with it.

Hassan Juma'a Awad, President of the Iraqi Federation of Oil Workers, in 2005.

Monday, April 6, 2020

WORK AND POVERTY IN THE DATE PALMS

WORK AND POVERTY IN THE DATE PALMS

Photographs by David Bacon

The Progressive, 3/30/20

https://progressive.org/dispatches/poverty-in-the-date-palms-bacon-200330/

These photographs document the date palm workers, or "palmeros". They are a window into their lives, showing their living conditions and the pain of exploitation. They document families, homes, and the culture of indigenous Purepecha people from the Mexican state of Michoacan - the main indigenous group in the farm labor workforce of the Coachella Valley.

In the Coachella Valley, where the date farms are concentrated, the industry brings in $65 million a year. Despite this, many Coachella farm workers live in trailer parks in colonias, or informal settlements, near the fields under the valley's intense sun. There are not many "palmeros" - perhaps only two hundred. Outside of Arabia, Iraq and North Africa, date palms are only grown here.

The work is dangerous - the palms rise from twenty to sixty feet above the sandy desert floor of the Valley. The photographs show the work process in which workers climb into the trees on ladders, or in more recent years on cherry pickers - mechanical lifts - and then walk around the tree's crown on the palm fronds as they work. In the course of a year, a "palmero" has to go up into the palm trees seven times.

The first operation is depicted here - the pollenization. Date palm trees are dioecious - they come in sexes. The flowers of the male palm produce the pollen. It is the female tree that produces flowers that become the seeds, and which therefore bear the fruit.

These photographs are part of a larger body of images and oral histories that I began in Coachella in 1992, and which continues today. The archive of this work is in the Special Collections of the Green Library at Stanford University.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2017 - Jose Cruz Frias, a "palmero", works in a grove of date palms. He climbs the trees on a ladder, and once up in the tree he walks around on the fronds themselves. This is one of seven operations that must happen to the trees each year to get them to bear fruit. Cruz has been doing this work for 15 years. He originally came to the Coachella Valley from Irapuato, Guanajuato in Mexico.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2017 - During this phase of the work, Jose Cruz Frias sprays pollen from a small bottle onto the buds that will become the dates, and ties the bunch together with string. This is one of seven operations that must happen to the trees each year to get them to bear fruit.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2017 - Jose Cruz Frias, a "palmero", points to scars on his hand from the knife and the spines of the tree.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2010 - Ana Sanchez lives in the St. Anthony's Trailer Park near Thermal, in the desert in Coachella Valley. The water supply of the park is contaminated, and Sanchez and the other residents have to get their drinking water from a tank.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2010 - Children in the St. Anthony's Trailer Park, in the desert in Coachella Valley.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2010 - Trailers in the St. Anthony's Trailer Park near Thermal, in the desert.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2017 - Alberto Castro works as a "palmero", in the date palm groves of Coachella Valley, and has worked over 15 years in the trees. After work he sits in the shade of the trailer where he lives in a trailer park near Thermal. He holds the safety harness he is supposed to use when working, but it restricts his ability to work quickly, and he is paid by the piece rate, so he often doesn't use it.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2017 - Carlos Chavez works as a "palmero", and has worked over 20 years in the trees. After work he sits in the shade of his trailer with his daughter Michelle. Michelle is in high school, trying to win a scholarship so she can go to college. Carlos took her to work with him one summer, but she didn't like it, and says it motivated her to study harder.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2010 - Meregildo Ortiz (l) is the president of the Purepecha community in the Coachella Valley. Purepechas are the main indigenous group in the Mexican state of Michoacan, and many live in the trailer camps in the desert near the Salton Sea. They work as farm workers in the fields of the Coachella Valley. Seated with him are Max Ortiz and Julian Benito.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2017 - Arturo Cordoba, an artist in the Desert View Mobile Home Park, outlines lettering he will carve into a wood plaque.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2010 - Members of the Purepecha community in the Coachella Valley gather at night to rehearse the Danza de Los Ancianos (the Dance of the Old People), preparing to perform it during a procession celebrating the Virgin de Guadalupe. This is also an opportunity to teach young people the dance and music traditions of the community.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2017 - The hands of Carlos Chavez, a "palmero", show the lines and creases of 20 years of hard work in the date palms.

Photographs by David Bacon

The Progressive, 3/30/20

https://progressive.org/dispatches/poverty-in-the-date-palms-bacon-200330/

These photographs document the date palm workers, or "palmeros". They are a window into their lives, showing their living conditions and the pain of exploitation. They document families, homes, and the culture of indigenous Purepecha people from the Mexican state of Michoacan - the main indigenous group in the farm labor workforce of the Coachella Valley.

In the Coachella Valley, where the date farms are concentrated, the industry brings in $65 million a year. Despite this, many Coachella farm workers live in trailer parks in colonias, or informal settlements, near the fields under the valley's intense sun. There are not many "palmeros" - perhaps only two hundred. Outside of Arabia, Iraq and North Africa, date palms are only grown here.

The work is dangerous - the palms rise from twenty to sixty feet above the sandy desert floor of the Valley. The photographs show the work process in which workers climb into the trees on ladders, or in more recent years on cherry pickers - mechanical lifts - and then walk around the tree's crown on the palm fronds as they work. In the course of a year, a "palmero" has to go up into the palm trees seven times.

The first operation is depicted here - the pollenization. Date palm trees are dioecious - they come in sexes. The flowers of the male palm produce the pollen. It is the female tree that produces flowers that become the seeds, and which therefore bear the fruit.

These photographs are part of a larger body of images and oral histories that I began in Coachella in 1992, and which continues today. The archive of this work is in the Special Collections of the Green Library at Stanford University.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2017 - Jose Cruz Frias, a "palmero", works in a grove of date palms. He climbs the trees on a ladder, and once up in the tree he walks around on the fronds themselves. This is one of seven operations that must happen to the trees each year to get them to bear fruit. Cruz has been doing this work for 15 years. He originally came to the Coachella Valley from Irapuato, Guanajuato in Mexico.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2017 - During this phase of the work, Jose Cruz Frias sprays pollen from a small bottle onto the buds that will become the dates, and ties the bunch together with string. This is one of seven operations that must happen to the trees each year to get them to bear fruit.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2017 - Jose Cruz Frias, a "palmero", points to scars on his hand from the knife and the spines of the tree.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2010 - Ana Sanchez lives in the St. Anthony's Trailer Park near Thermal, in the desert in Coachella Valley. The water supply of the park is contaminated, and Sanchez and the other residents have to get their drinking water from a tank.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2010 - Children in the St. Anthony's Trailer Park, in the desert in Coachella Valley.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2010 - Trailers in the St. Anthony's Trailer Park near Thermal, in the desert.

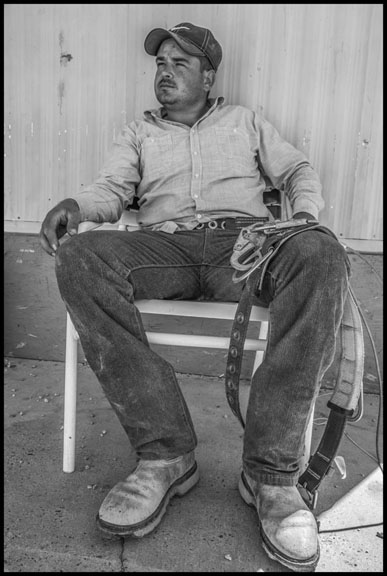

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2017 - Alberto Castro works as a "palmero", in the date palm groves of Coachella Valley, and has worked over 15 years in the trees. After work he sits in the shade of the trailer where he lives in a trailer park near Thermal. He holds the safety harness he is supposed to use when working, but it restricts his ability to work quickly, and he is paid by the piece rate, so he often doesn't use it.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2017 - Carlos Chavez works as a "palmero", and has worked over 20 years in the trees. After work he sits in the shade of his trailer with his daughter Michelle. Michelle is in high school, trying to win a scholarship so she can go to college. Carlos took her to work with him one summer, but she didn't like it, and says it motivated her to study harder.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2010 - Meregildo Ortiz (l) is the president of the Purepecha community in the Coachella Valley. Purepechas are the main indigenous group in the Mexican state of Michoacan, and many live in the trailer camps in the desert near the Salton Sea. They work as farm workers in the fields of the Coachella Valley. Seated with him are Max Ortiz and Julian Benito.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2017 - Arturo Cordoba, an artist in the Desert View Mobile Home Park, outlines lettering he will carve into a wood plaque.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2010 - Members of the Purepecha community in the Coachella Valley gather at night to rehearse the Danza de Los Ancianos (the Dance of the Old People), preparing to perform it during a procession celebrating the Virgin de Guadalupe. This is also an opportunity to teach young people the dance and music traditions of the community.

COACHELLA VALLEY, CA - 2017 - The hands of Carlos Chavez, a "palmero", show the lines and creases of 20 years of hard work in the date palms.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)