FRED HIRSCH: DOING THE WORK THAT NEEDED TO BE DONE

By David Bacon, December 28, 2020

Stansbury Forum, https://stansburyforum.com/2020/12/28/fred-hirsch-doing-the-work-that-needed-to-be-done

Organizing Upgrade, https://organizingupgrade.com/fred-hirsch-doing-the-work-that-needed-to-be-done/

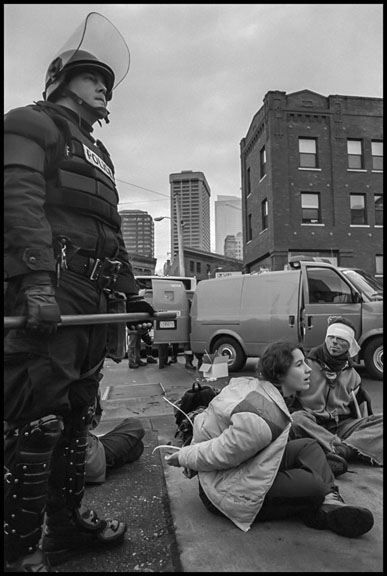

Together with immigrants, workers, union members, people of faith and community activists, Fred sat down in the street in front of the Mi Pueblo market in East Palo Alto, calling for a moratorium on deportations and the firing of undocumented workers because of their immigration status. 2014

Fred Hirsch, born in 1933, died on December 15, 2020 in San Jose.

When Adriana Garcia heard about his death, it was a blow. “The whole South Bay is hurting,” she mourned. Garcia heads MAIZ, a militant organization of Latina women in Silicon Valley. For many years she and Fred co-chaired the annual May Day march from San Jose’s eastside barrio to City Hall downtown.

The recovery of May Day was one of the great political changes that took place during Fred’s lifetime. May Day commemorates the great demonstrations in Chicago in 1886 for the eight-hour day, and the execution of the Haymarket martyrs a year later for leading them. When Fred became a political activist and Communist in the 1950s, the holiday had become virtually illegal, a victim of Cold War hysteria. It was called the “Communist holiday,” celebrated everywhere in the world but here.

Fred grew up in New York, where police on horseback attacked the May Day rally in the city’s Union Square in 1952. They clubbed down mothers with strollers who were holding signs calling for justice for Willie McGee, a victim of legal lynching in Mississippi. Years later it was no surprise that Fred helped organize a local support network for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. SNCC fought the racism and political repression in the South that killed McGee, and its courageous student activists helped end the dark years of McCarthyism.

Even by the 1970s, fear of redbaiting still kept most delegates away from the May Day events Fred would organize among delegates to the Santa Clara County (now South Bay) Labor Council. In 2006, though, everything changed. Millions of immigrants chose May Day, a holiday they knew well from back home, to pour into the streets, protesting a law that would have made it a felony to lack immigration papers. Tens of thousands marched in San Jose. In the years that followed, when Fred and Adriana asked unions to come out for May Day, they’d bring banners and arrive by the busload.

To Fred, May Day wasn’t merely a radical symbol. It was a chance to connect union and community activists in San Jose to people far beyond the country’s borders, and to talk about a shared set of politics. Making those connections, seeing the world joined by the bonds of a common class struggle, was the thread that ran through Fred’s politics throughout his life.

I interviewed Fred not long before his death, to understand the political history of Silicon Valley, and his own work that helped shape it. Because Fred had been a “big C” Communist for most of his life, and a “little c” communist to its end, he viewed his long activity, not as the work of one person alone, but as the product of a history, of a set of ideas, and of a collective of people fighting together.

‘LITTLE OCCURRED SPONTANEOUSLY’

“A thread runs through Santa Clara Valley’s history of labor and community organizing,” he explained, “from the days of the canneries up through the heyday of industrial production in the high tech industry. Very little organizing or political activity occurred spontaneously. There was always a small group of left-wing, class-conscious, Marxist-oriented workers who met regularly, exchanged experiences, and planned campaigns.

“It was not one single group. New people came in and others moved on. Many simply got old, retired and died. Through much of the time an important strand of that thread was the Communist Party and the many friends with whom its members worked. But other groups with similar left ideas also organized and sought to influence people.

Fred came with his union banner and members of Plumbers Local 393 to the huge march to support the drive to organize the strawberry workers in Watsonville. 1997

Fred spent his working life as a plumber and pipefitter, after joining the union in New York in 1953. Being in the union brought political responsibilities – to defend it and the labor movement, and at the same time to fight for politics that represented the real interests of workers. At 20 that meant opposing the Korean War, calling for peace with the Soviet Union, and opening the union’s doors to Black workers. The local’s leaders told him plainly that once he passed his apprenticeship, they wanted him out.

He left New York with his wife Ginny and migrated to California. Leftwing politics kept him from getting work in Los Angeles as well, so they moved north. In San Jose Fred still faced redbaiting, but Communists hadn’t been driven out of the local labor movement and their presence helped the family survive. Fred also knew that survival depended on winning the respect of the plumbers he worked with. In a tribute to him after he’d been a member of United Association (UA) Local 393 for 50 years, Fred was called “a good mechanic” – plumber-speak for a worker who knows his job.

Transforming the labor movement – making it not just more militant, but anti-racist and even socialist – was the ever-present idea. Sometimes it meant organizing a trip with other unionists to show support for newspaper strikers in Detroit. Sometimes it meant going to Colombia to expose U.S. support for a murderous government and paramilitaries out to obliterate the union for oil workers. Sometimes it just meant showing up at a farmworkers boycott picket line in front of Safeway, in his VW van full of copies of the Communist newspaper, the People’s World.

Transforming the labor movement was part of Fred’s hope when he, Ginny and their daughter Liza moved to Delano in 1967, after the grape strike had been going on for two years. “The work they were doing in Delano,” he later remembered, “led me to hope that one day farmworkers could stimulate a transformation of our rather moribund AFL-CIO into a real labor movement. It seemed achievable. The organization of ill-fed, ill-housed, and ill-clothed agricultural workers, who truly had ‘nothing to lose but their chains and a world to win’ could change the shape of the workers’ struggle in California. Farmworkers, in their hundreds of thousands, could potentially provide a model of workers’ power that could lead organized labor into a new and militant era.”

Fred and some of the workers fired at the Mi Pueblo market because of their immigration status went into the store to confront managers and security guards, demanding their jobs back. 2011

Fred was physically courageous, and was beaten by foremen and strikebreakers as he went into fields, ostensibly to serve legal papers, but in reality to organize. Having been roughed up in his own union by fearful and angry right-wingers, someone should have told the scabs it would only make him more determined, and it did. But even in Delano he faced redbaiting, when the leaders of the then-called United Farm Workers Organizing Committee wouldn’t give him a real assignment. He called it “an anti-ideological hand-me-down from the prejudices of Saul Alinsky.”

But soon he was working with older Filipino workers, the “manongs,” chasing railroad cars shipping struck grapes out of Delano and the San Joaquin Valley. In order to track their movements and stop them, “We were to call a special number and report our whereabouts to our Filipino brothers, who would move pins on the map to follow the progress of the grapes.” In these old men Fred knew he’d found veterans of decades of strikes in the fields, going all the way back to the 1930s. He also knew he’d found a group of workers, Communists among them, who despite their age brought radical politics into the early United Farm Workers.

POWER COMES FROM THE BASE

Fred always had his eyes on the workers at the base of any union. He pinpointed early on the problems in the UFW’s structure that would ultimately weaken it. “There was a weakness in what I saw in Delano,” he recalled later, “that kept gnawing at me. Yes, the workers were getting organized, but they were not necessarily organizing themselves.” Fred’s politics inherited a set of principles from the Communist, socialist and anarchist traditions in the U.S. labor movement – that the power in the union comes from workers at the base who should control it, and that the more politically conscious those workers are, the greater capacity for fighting the union will have.

Finally, he and Ginny left Delano when Robert F. Kennedy won the union’s support for his presidential campaign. Fred later acknowledged that if Kennedy hadn’t been assassinated, the union would have won crucial support it needed in Washington. But he and Ginny remembered Kennedy as an aide to Senator Joe McCarthy, and later as the author of deregulation that destroyed much of the power of organized truckers. Even though Liza was later brutally redbaited and purged from the UFW, Fred continued to support the efforts of farmworkers themselves. “The UFW helped shape the life of our family,” he said. “Whatever its failings or accomplishments, it nurtured and developed a generation of organizers and activists who continue to make a positive impact on trade unionism and the political life of our nation.”

Fred speaks at a rally at City Hall at the end of the May Day march. 2010

ORGANIZING IN THE COMMUNITY

Back in San Jose Fred was a key organizer of the huge upsurge of the civil rights and anti-war movements that transformed the politics of the Santa Clara Valley. His comrade-in-arms was Sofia Mendoza, who with her husband Gil and other Chicano community activists in the San Jose barrio began organizing against the Vietnam War.

The first of the student blowouts, which helped launch the Chicano movement, took place at San Jose’s Roosevelt Junior High in 1968. That led to student walkouts in Los Angeles, and eventually to the huge Chicano Moratorium march against the Vietnam War up Whittier Boulevard. In San Jose the movement began organizing marches on City Hall, and formed a committee to stop police brutality, the Community Alert Patrol (CAP). “The police had guns, mace and billy clubs,” Mendoza remembered. “They were always ready to attack us. It seemed as if nobody could stop what the police were doing.”

But CAP did stop them. Its members monitored police activity, much as the Black Panthers were doing in Oakland, documenting police beatings and arrests. Students organizing for ethnic studies classes at San Jose State University became some of CAP’s most active members, at the same time fighting to get military recruiters off the campus. CAP had the participation of Communists, socialists, Chicano nationalists and other leftwing groups.

Sofia, Fred and others believed San Jose needed a multi-issue organization to confront the many problems people faced in the barrios – discriminatory education, lack of medical services, poor housing, and of course the police. “We wanted an organization that was not limited to one ethnic group, that would organize our entire community,” she later recalled. “We called ourselves United People Arriba – United People Upward -because it got the idea across that people from different ethnic backgrounds were coming together in San Jose to work for social change – Blacks, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans and whites working together in one organization.” Today Silicon Valley De-Bug’s Albert Covarrubias Justice Project, the community organizing of Somos Mayfair, and the Services, Immigrant Rights and Education Network all carry on the legacy of CAP and UP Arriba.

In 1972 Angela Davis, African American revolutionary feminist and then-leader of the Communist Party (CP), went on trial in San Jose, charged with kidnapping and murder, accused of providing the guns used by Jonathan Jackson in an attempt to free his brother, George, a leader of the Black political prisoners’ movement. Davis’ historic acquittal was the product of an international campaign that succeeded because a strong local committee mobilized support. Ginny Hirsch, assisted by Fred, researched every person named as a potential juror, work that ensured the jury included people open and fair about the prosecution’s false accusations. This kind of community research has since become a powerful tool in other trials of political activists.

On the first day of a three-day hunger strike to protest the firings of workers because of their immigration status, Fred speaks at a rally in downtown San Jose. 2010

FIGHTING DEPORTATIONS

The South Bay’s first fights against deportations began with the government’s effort to deport Lucio Bernabe, a cannery worker organizer. His defense was mounted by the American Committee for the Protection of the Foreign Born, put on the Attorney General’s list of “subversive organizations.” Further fights against raids in Silicon Valley electronic plants like Solectron, and garment factories like Levi’s, led Fred and other activists to oppose the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986. Although the law provided amnesty to undocumented people, which they supported, activists warned that the law’s prohibition on hiring workers without papers would lead to massive firings and attacks on unions. The law also reinstituted the hated “bracero” contract labor program, which Fred’s compañeros Bert Corona and Ernesto Galarza had fought all through the McCarthyite years.

In fighting IRCA, Fred challenged the AFL-CIO’s support for the bill, along with other beltway advocacy groups in Washington DC. They argued that if undocumented people were driven from their jobs and couldn’t work, they’d go home and leave the jobs to “us.” Fred and his cohorts lost the battle when the law passed in 1986, but continued to organize until they succeeded in 1998, when the AFL-CIO reversed its position, and called for amnesty and labor rights for immigrants. When similar immigration bills were introduced in years afterwards, Fred again defied the liberal Washington DC establishment and supported instead the Dignity Campaign for an immigration policy based on immigrant and labor rights.

UNMASKING AFL-CIO/CIA TIES

In 1973 Chileans began to arrive in San Jose, and Father Cuchulainn Moriarty made Sacred Heart church on Alma Street the resettlement center for those who fled the fascist coup. Enraged, not just at the CIA’s organization of the coup, but at the deep complicity of the AFL-CIO’s International Department, Fred wrote one of the most damning exposes of its work, “An Analysis of our AFL-CIO Role in Latin America, or Under the Covers with the CIA.”

In just a relatively few pages, he did more than document the sordid history of the AFL-CIO’s support for fascism in Chile. The small pamphlet became the tool used by leftwing labor activists for many years, in the long struggle to cut the ties between the U.S. labor movement and the anti-communist intelligence apparatus of the government.

Fred marching in San Francisco, opposing U.S. intervention in El Salvador. 1990

It was a long fight. In 1978 the first Salvadoran Communists and trade unionists appeared in San Jose, looking for help after the U.S. supported the Salvadoran government, and trained its death squads at the School of the Americas. It was the beginning of the Salvadoran civil war, and over the next decade two million Salvadorans sought refuge in the U.S., ironically, for what the U.S. itself was doing to their country. The first Salvadorans fleeing the death squads deployed against unions in the late 1970s sought out the Hirsch home on 16th Street. To expose what had made them flee, Fred and his comrades organized the Labor Action Committee on El Salvador, a forerunner of CISPES, the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador. Their work was so effective that when they invited Salvadoran leftwing trade unionists to come to the U.S. as guests of the South Bay Labor Council, the AFL-CIO’s president George Meany threatened to throw the council into trusteeship.

Mexican miners came north during a bitter strike at the huge Nacozari copper mine in Sonora, finding money and friends in San Jose. Fred went to Colombia and came back with another long report. He told labor council delegates, “I’m a retired plumber who’s been around the block a few times. I’m not easily moved, but in Colombia I saw a daily life reality I’d only glimpsed before, mostly in nightmares … We have to stop sending our taxes and soldiers to protect corporate interests in Colombia.” And when unions were pressured to supporting President George H.W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq, he responded by convincing his plumber’s local to send money to start U.S. Labor Against the War.

These were all solidarity actions from below, not only intended to provide support for workers themselves, but to show to the members of his own union the consequences of the actions of U.S. corporations, and the imperial system from which they profit. In Fred’s way of organizing, solidarity was a way to help his fellow pipefitters understand that the unions of Mexico, Chile or El Salvador were their true allies, and to reject the idea that unions here should defend a system that attacked them.

ORGANIZATION IS VITAL

Fred was not a voice in the wilderness, however, speaking out by himself. He saw a common interest between immigrants and native-born, between workers of color and white workers, between unions in the U.S. and those around the world. He never stopped trying to explain that class gave them something in common, and he found effective ways to convince white workers in particular that fighting racism and imperialism was in their own interest. Whether organizing for a progressive immigration policy or for solidarity with leftwing unions in El Salvador, Colombia and Iraq, he brought his own union’s members with him, along with delegates to his labor council, progressive elected officials, and many others.

Fred supported every significant social movement that arose in the South Bay for over six decades, but he never believed that a spontaneous upsurge would suddenly defeat capitalism. He believed in organization, not just of unions and communities, but of political activists. For many years he thought those activists could find a political home and education in the Communist Party, and an organization capable of planning a lifetime struggle to win socialism. At the end of his life he was no longer sure that the party was that organization, but if not the CP, some organization would have to play that role, he thought.

“It would have to have a clear focus on a socialist and democratic future in a world without war,” he told me at the end of our conversation. “It would have to fight injustice in our communities and worksites, our nation and our planet, promote serious education about the process for social change and organize people to take to the streets.”

Real revolutionaries in his beloved labor movement, he thought, need to band together to fight racism and sexism “all through the institutions and culture of our society.” And in doing all this, they should be humble, willing to do the work that needs doing, and glad to take leadership from the people around them. In short, Fred wanted “an organization like the Communist Party we dreamed and worked for so many years ago, but more effective than we were. Without it wonderful working class leftists will continue making enormous efforts to build progressive movements that ebb and flow, but won’t develop a strategy and build a base of their own.”

In the outpouring of messages from activists hearing of his death, it was apparent that plenty of people had absorbed Fred’s ideas. Virginia Rodriguez, the daughter of farmworkers and a lifetime labor organizer like him, passed away before he did. But she shared his confidence in a vision of an ongoing core of politically committed activists. “I came to believe,” she said, “that there will always be those individuals who will respond to the outer edges of what needs to be done, and who will step forward to take up responsibility for what is called for if change is to take place. In so doing, these people help move others to come along. It underscores the principle that if enough of us carry out a piece of what needs to be done, then change will most certainly come.”

Adriana Garcia, eight months pregnant, with members of MAIZ in the same May Day march, which she co-chaired with Fred. 2010

Thanks to the Farmworker Movement Documentation Project for preserving the memories of Fred Hirsch, Virginia Rodriguez and many others of their experiences working with the United Farm Workers.

All photographs are Copyright David Bacon.

This article is being published jointly by Organizing Upgrade and The Stansbury Forum.