VIETNAM'S LABOR NEWSPAPER

Where a Staff of 200 Reports on Abuses at Home and Abroad

Lao Dong belongs to the official union federation, but it maintains an independent critical voice.

By David Bacon

The Nation, 3/30/16

http://www.thenation.com/article/vietnams-labor-newspaper-where-a-staff-of-200-reports-on-abuses-at-home-and-abroad/

The road from Hanoi to the airport and south to the coast crosses the Red River a few miles from the Long Bien railroad bridge. Forty-five years ago, US B-52s bombed it repeatedly, pounding it with more explosives than were ever dropped on any Nazi factory in World War II. Today, trucks and motos crowd a multi-lane highway running atop the dikes. Below it, neat fields of bananas and vegetables spread to the edges of new towns-multi-story houses and apartment blocks rising suddenly from the flat delta landscape.

As Vietnam moves further down the road of a market economy, old and new collide in every aspect of life. People drive to the airport on a freeway, but mostly on scooters, not in cars. That might be better for the environment, but double and even triple lines of parked scooters already choke the downtown sidewalks. Bicycles are still part of the traffic mix, but people's expectations about how to get around have moved way beyond them. A working couple can have their wedding photo taken in front of Hanoi's Prada outlet, whose display rivals anything on Union Square in San Francisco. But who can afford to buy anything inside? Buildings go up, but housing costs force lots of young adults to live at home with their parents.

Vietnam's history with the United States is woven into all these contradictions. Ho Chi Minh quoted our own Declaration of Independence in Vietnam's 1945 independence proclamation; its 70th anniversary was celebrated last year. Despite that tribute, the United States first funded the reinstallation of the French colonial regime from the end of World War II to its defeat at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. Then the United States, together with symbolic forces from a few anti-Communist allies, fought one of the bloodiest wars in its history against Ho and the Vietnamese revolution. The United States was forced to withdraw its troops in 1973, and the South Vietnamese government it funded fell in 1975, after which the country was reunited.

Postwar, the market economy was launched in 1986, but it only really took off after President Bill Clinton dropped the US trade embargo in 1994. Vietnam and Washington signed their first trade agreement in 2000.

Now, with the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) multilateral trade agreement on the horizon, economic integration will likely have as great an impact on the people of both countries as NAFTA did on workers in the United States, Canada, and Mexico. And just as that trade agreement produced closer cross-border relationships between labor in the NAFTA countries (although this was not the intention of the treaty's corporate authors), some US and Vietnamese activists would like to see similar relationships develop across the Pacific.

"Increasingly, the same multinational corporations are operating in both our countries, and our economies are more integrated," says Kent Wong, director of the UCLA Labor Center and vice-president of the California Federation of Teachers. "We need to work together to defend worker rights and economic justice. The Vietnam War ended 40 years ago. In those years millions of people in this country stood with the people of Vietnam for peace. That same spirit of solidarity is needed to support a common agenda for peace and justice today."

American unions, however, know very little about Vietnamese workers or the country's labor movement. It might surprise unionists here, for instance, to discover that Vietnam not only has a labor newspaper, Lao Dong (Labor), but that it has a staff of about 200. It's a mainstream publication and the second most widely read newspaper in Vietnam, with a print run of 40,000 and another 200,000 digital subscribers. And Lao Dong has deep roots, having been published since 1930. This is in remarkable contrast to the United States, where we have no national labor newspaper.

Lao Dong is published by the Vietnam General Confederation of Labor (VGCL), the country's official union federation. It was founded as the Red Federation of Trade Unions in 1929, part of the resistance movement to French colonialism, and has had a close relationship with the Vietnamese Communist Party from the beginning. Its president, Dang Ngoc Tung, is a member of the party's central committee. Under Vietnam's labor law, all unions must belong to the VGCL, although language in the TPP may end that requirement. The federation has about 9 million members, about half the country's estimated 18 million wageworkers, in an economically active population of 50 million.

Lao Dong, however, gets no subsidy from the VGCL, and its budget is paid by ads and subscriptions. "That gives us our independence," says its editor-in-chief, Tran Duy Phuong. Last year the paper needed its independence. Throughout 2014, it had published a series of stories about the abuses suffered by Vietnamese migrant laborers working abroad. Many stories were based on investigations by reporters of letters, e-mails, and phone calls on its hotline from relatives of people working as contract laborers, especially in Saudi Arabia.

One came from Ms. Le Thi Bien, whose sister Le Thi Khanh left Vietnam in October 2014 for a job as a domestic worker in Riyadh. "My sister had to work constantly, even at night, with no time to rest," Bien wrote. "She got an eating disorder due to the stress of being insulted all the time." When she asked for her pay, the son of the family employing her held a gun to her head.

The family tried complaining to Vietnam's Department for Management of Overseas Labor, part of the Ministry of Labor, Invalids, and Social Affairs (MOLISA), but got no reply. Lao Dong reporters tracked down the recruiting company based in Vietnam, whose representative, Lai Thi Ha Thu, claimed the incident "wasn't deliberate intimidation or malice, just joking." The government labor department admitted it had no representatives in Saudi Arabia to monitor conditions. The case caused an uproar in the Phu Tho province, where Khanh's family lives, and the provincial labor federation there demanded tighter restrictions on labor contractors in the law governing recruitment of foreign workers, and monitoring by the government to ensure better treatment.

Other domestic workers reported similar abuse. In Saudi Arabia, To Thi Dung had to wake up at 6 every morning and work until 2-3 AM the next day. After two months of nosebleeds, vertigo, and dizziness, she told her family in Vietnam she couldn't take it anymore. Focusing on labor contractors, Lao Dong showed that Dung's recruiter, Hai Duong Branch, was given government certification to recruit laborers to foreign countries, despite the reported mistreatment. When Dung asked to go home, she was threatened and her family had to borrow 23 million dong (over $1,000) to compensate the company for breaking her two-year contract.

Another Vietnamese overseas worker, Ma Thi Yen, was beaten, sexually abused, and had to work 16 hours a day. After she wrote to Lao Dong, the paper exposed her mistreatment and Yen finally received 23 million dong from the contractor, but her mother-in-law told a reporter, "I would rather my child stay home, eat vegetables with vegetables, or porridge with porridge, than ever dare think of leaving as a migrant laborer."

Lao Dong eventually sent three teams of reporters to countries where Vietnamese women were working as domestics, developing its main story on semi-bondage conditions in Malaysia. As a result of it, 200 women were freed there and repatriated to Vietnam.

The articles stirred up controversy. "We got pressure for running the stories," says editor-in-chief Phuong. "A lot came from the recruiting agencies, who weren't taking responsibility for the conditions faced by people they'd recruited. But we also got pressure from the embassies and the higher-ups." Authorities were embarrassed over the exposé of their failure to protect workers abroad. The paper was accused of endangering the government's labor-export policy and its increasing dependence on foreign remittances, which in recent years reached $2 billion annually, according to a report by the International Labor Organization.

That report found an extensive network of labor brokers, placement agencies that recruit the workers, and even individual agents in rural areas working for the recruiters. Workers are very vulnerable in this system. They have to pay fees to the labor brokers and leave a large deposit to guarantee they'll work to the end of their contract. Quitting or getting fired can be an economic disaster. MOLISA is responsible for licensing labor recruiters in Vietnam and for regulating and monitoring their activity and fees. The department is also responsible, however, for expanding the overseas market for Vietnamese labor by signing contracts with foreign employer groups, while at the same time enforcing minimum standards. That can produce a conflict of interest, since aggressively protecting workers can lead foreign employers to find sources of workers from other countries that cause fewer problems or are willing to accept lower wages.

* * *

Migration is not a new issue in Vietnam. Its domestic population is 93 million, and about 4 million Vietnamese live abroad. In the years following the American War (as Vietnamese call it), most of those who left the country did so as refugees. During the Cold War, tens of thousands of Vietnamese also studied and worked in the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, the German Democratic Republic, and other then-socialist countries. Many stayed on afterward and live there still. According to the (US) Migration Policy Institute, Nguyen is now the ninth most common surname in the Czech Republic.

After the 1986 Doi Moi economic reforms loosened restrictions on emigration, the number of people leaving Vietnam as contract workers rose sharply. In 2000, the government reported that 118,000 people were working abroad as migrants. The number went up by 5.5 percent a year from 2000 to 2010, and shows no sign of slowing.

Like many developing countries, Vietnam has become a labor exporter. In 2014, over 100,000 Vietnamese got jobs in Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar. This growth is partly a result of limited employment at home, partly of international wage differentials. A million and a half young Vietnamese enter the labor force each year, and the economy, despite an average 6.5 percent growth rate, can't produce jobs for them all. Vietnam is not the country with the lowest wages in Southeast Asia-agricultural labor in Malaysia, for instance, pays less than Vietnam's lowest wages, and garment jobs in Bangladesh pay even less. But a domestic job in the Middle East can pay what a good job in Vietnam might-$300-400 a month. A factory job in South Korea or Japan can pay $700-900.

To get those jobs, many families pay huge fees or bribes to labor contractors-the system investigated by Lao Dong. Despite glowing promises, the paper found a sordid record of unpaid wages, withheld passports and earnings, filthy labor camps where workers were virtually imprisoned, and other abuses.

* * *

Lao Dong reports on labor abuses in Vietnam as well. Five years ago it won a national prize for a series about workers in private coal mines, called "Pirate Mines." After workers sent letters to the paper denouncing dangerous conditions, the paper sent reporters to work undercover to investigate. Coal operators later put a $5,000 price on the head of the lead reporter for exposing the abuses.

According to Angie Ngoc Tran, political economy professor at California State University Monterey Bay, "The Lao Dong newspaper, a dynamic pro-labor press, has been covering the strikes and worker grievances throughout Vietnam closely. They have journalists stationed in Ho Chi Minh City who go to the strike scene on a daily basis to cover the strikes and report them promptly to support workers. However, because this newspaper belongs to the VGCL, Lao Dong has to walk a delicate balance between championing workers' rights and promoting the interests of the state and the labor unions."

When 90,000 workers struck foreign-owned factories in Ho Chi Minh City in March 2015, one was quoted declaring, "With the wage of 3.48 million dong/month [about $167], every month I pay 380,000 dong to the social insurance fund. If I work for 10 more years, until I reach 40, I no longer have good health [enough energy] to work."

"Our method of work is to first pay attention to what workers tell us," one Lao Dong editor told me. "We'll verify the information we're given, and then assign a reporter to follow up." If there's no danger to the workers, and with their consent, the paper will use their names. But it will protect the confidentiality of its sources if necessary. According to Vietnam's media law, reporters don't have to provide the names of sources unless they are demanded by a national government prosecutor. Chief editor Phuong says Lao Dong has had many fights prosecutors over the disclosure of sources.

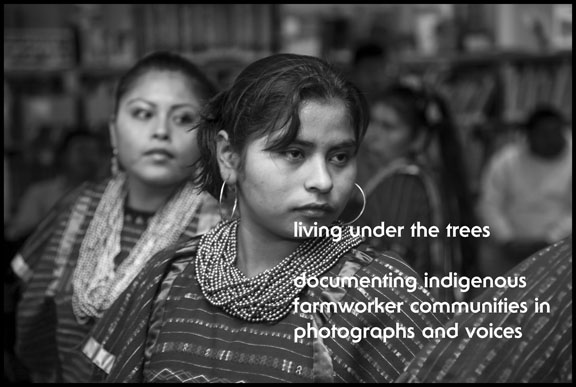

Photographs in Lao Dong also document the lives of working people. Some come from workers themselves, but staff photographer Duong Quoc Binh also develops full-page photo-essays. Not all are about labor disputes. A recent one looked at the indigenous custom of fire-walking, which dates back 3,000 years to India and Sri Lanka. "Today the Pa Then ethnic people in Ha Giang Province celebrate this festival from October's first full moon to the end of January," he says in the introduction to the photo-essay.

Photo by Duong Quoc Binh, courtesy of Lao Dong

The most prominent photo in the series shows sparks flying in a night-time scene, while a silhouetted figure walks across the burning ground. Its most dramatic images show the soles of the feet and the palms of the hands of dancers, gray with the ash from coals. The young people who participate are paid 200,000 dong (less than $10) for their labor by the religious figure who organizes the event.

Workers at Lao Dong belong to the Vietnam Public Sector Union. Like most unions in socialist countries, its members include people in management. In US labor law, management is excluded from unions that represent workers. Most US unions feel that a union would not be able to fight for workers with complaints or grievances if the managers creating problems were also union members, nor would the organization be able to successfully fight for better wages and conditions.

According to Chau Nhat Binh, who recently retired as the deputy director of the international department of the VGCL, wages for a reporter at Lao Dong start at about $500 per month and can go up to $2,000. When workers have complaints against a manager in their own workplace or disagree with a decision, they can go to an inspectorate, or audit committee. "They quite often overrule the manager," Binh says. "Three years ago, workers at Lao Dong were unhappy with the then-editor in chief. They went to the inspectorate, and eventually were able to remove him."

Other pressures faced by Lao Dong workers would sound familiar in a US newsroom or to freelancers here. Staff reporters and photographers are expected to multitask-that is, to write and take pictures, and post material on the paper's website and blog. Over the years, women pushed for more and better jobs, and today, Lao Dong's staff includes more women than men. And while it has 200 permanent full-time employees, the paper also uses material from about 50 freelancers. Some are regular contributors and are covered under its labor agreement, but occasional contributors are not.

Despite their differences, both US and Vietnamese unions are worried about the impact of the TPP and corporate domination of trade and investment policy. "I'm really not sure about the promised benefits of TPP," Binh says. "It sounds like investors will certainly benefit, and the garment industry will expand, but what will the benefits be for workers?" The VGCL has been actively organizing workers in the foreign-owned factories for the past five years, he explains, and the federation's membership has grown. He wonders whether the intention of the TPP's prohibition on a single union for all workers is an invitation to set up rival unions.

Kent Wong of UCLA has even sharper doubts. "TPP is a pro-corporate trade agreement that lacks worker-rights protections," he emphasizes. "It's also a US-led corporate and military alliance to oppose China." The agreement has the formal support of the VGCL, which is tied politically to Vietnam's governing Communist Party and formally supports its policies. But Wong cautions that "many Asian labor unions, including those in Vietnam, feel compelled to participate given the economic pressures on their countries and their need to seek foreign investment."

The most effective response, Wong believes, is solidarity: "Now more than ever, the US labor movement needs to strengthen global solidarity in the Pacific Rim, and propose alternative trade policies that support worker rights."